“Someone stole the world and packed it up in a briefcase.”

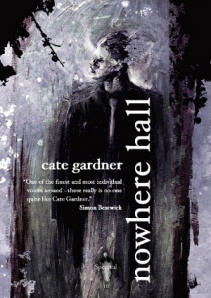

We all know how to deal with ghosts (salt, prayers, just move out of the friggin house already), vampires are old hat (stake, decap or wait til sunrise for the sparklies) and no matter what new permutation on zombies you may come up with, we have our plans ready (we won’t go into that). Physical threats are blasé, but many of us have to face a new horror: economic uncertainty. Yes, this is nothing new for the blue collar world (Braunbeck’s “Union Dues” pretty well sealed that one up for us), but now those who had always felt safe behind a desk aren’t so secure anymore. White collar Willy Lomans litter the pavement and we all know that we might be next. Enter Kate Gardner’s novella Nowhere Hall to poke and prod at this new chink in our psychological armor.

Meet Ron. We’re not sure where he’s going or even where he’s been, but neither is he. We just know that this poor soul seems snapped in a few places and that he’d been let go because he’s let himself go. His world seems familiar enough, but its logic doesn’t work quite right, things don’t make the sense that they should. And he finds himself at the door of a building, crossed with police tape and heralded by a falling umbrella with a simple note attached: We want to live. Help us.

In a way, Nowhere Hall can be looked at as an inwardly aimed ghost story that twists reality, in the same vein as Poppy Z. Brite’s Drawing Blood. It is surreal, but in a way that slips through the spaces between dendrites rather than slamming against the forebrain, shouting “Ooooh booga booga. I’ve got a marshmallow in my eyes!” Cate paints Ron as one who haunts as much as he is haunted, an empty shell roaming halls that have long forgotten him, and the effect is emotionally devastating. In this case, the slipstream flow of illogic is used to great effect in reflecting the inward confusion that Ron is experiencing as his world dissolves instead of simply being used for shock value.

Yes, if you prefer your narratives to be of the more direct variety, then you will not enjoy yourself here. It certainly took me several attempts rereading whole paragraphs multiple times to make sense out of the situation. But, as I said before, that’s the point. It should be confusing and disconcerting, it needs to be. It also isn’t a particularly cheery tale, ending with a question none of us really want answered (I want to say that we do, Cate, but I’m too afraid to find out the truth). However, the resulting experience is well worth it all.

Nowhere Hall ends up as a journey that is bewildering and heartbreaking, a painful search for worth where objective value has been removed that would fit perfectly along side of Tom Piccirilli’s Every Shallow Cut (read the review here), if you have a favorite razor you’d like to cuddle up with.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews