For this chapter in Horrifying History we’re focusing on the groundbreaking, but sadly overlooked, 1931 film M and the devil’s brigade of real life monsters that inspired it. Fritz Lang’s M is a remarkable accomplishment on multiple levels, and, like all those we’ve featured, it’s inspired by grisly real-life events. This time we’re traveling back to Germany’s post World War One Weimar Republic. If you ever wanted to build a fantasy football league for serial killers you’d find all your top draft picks prowling the streets of Weimar era Berlin.

But it’s not all about maniacs because this true horror tale actually has a real life hero—a visionary detective who became the world’s first criminal profiler.

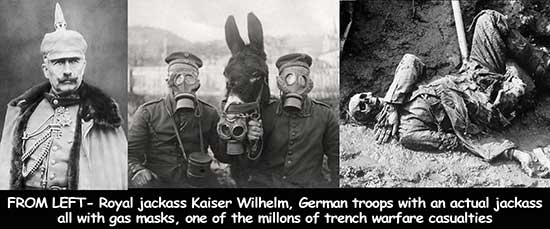

To set the stage here’s a semester of world history reduced to one paragraph. In the early 20th century, Europe’s political landscape had more inbred kings, emperors, czars and prince regents than an episode of Game of Thrones, all ruling by birthright rather than ability. Germany’s Kaiser (that translates to emperor) Wilhelm was the biggest pinhead of this Oedipal bunch. In 1914, Germany entered what was then called The Great War, which, after turning out to be anything but great, was given the optimistic name The War to End All Wars, only to be rechristened World War One following its even more horrendous sequel. Germany started off strong, racking up a string of military victories. Eventually the war turned sour, but the kaiser assured his people Germany would triumph. He also told them that cattle feed and sour turnips were a healthy alternative to meat and vegetables, which should have been a tip-off. By 1918, over half of Germany’s eleven million soldiers were either dead or crippled and even a congenital moron like Kaiser Wilhelm had to admit defeat. The kaiser was booted out of office and exiled to the Netherlands.

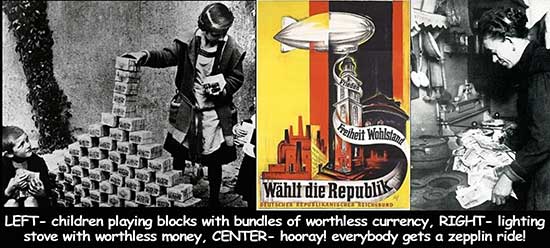

Following the armistice there was a revolution with everyone from communists to anarchists trying to take power. When the dust finally cleared, the surprisingly progressive Weimar Republic was born. But things got off to a shaky start with Germany’s currency becoming so devalued that it was more valuable as kindling than money. Then came recession, depression, starvation, and social unrest. If you want to know more about this amazing passage in history check out Dan Carlin’s compelling audio history Blueprint for Armageddon.

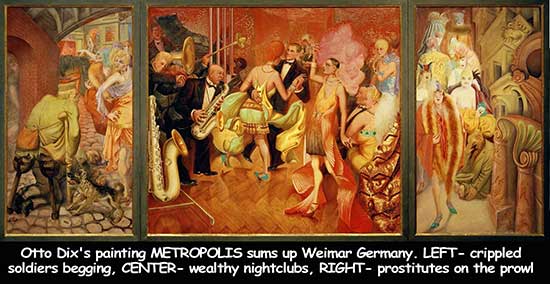

Historically, this kind of social chaos often spawns explosions of artistic expression, and Weimar Germany was no exception. The groundbreaking works of Brecht and Weil dominated the stage, while the Bauhaus Movement reinvented everything from painting to architecture. Decadent nightclubs welcoming straight, gay and transgender patrons alike sprang up, offering previously verboten spectacles like striptease and drag shows. And, of course, there was that upstart visual art form known as cinema. German filmmakers discovered that the horror genre was an ideal medium for their visual ideas. Audiences and art critics alike embraced expressionistic works like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). Nosferatu (1921) invented the vampire film while 1920’s The Golem: How He Came into the World paved the way for Hollywood’s Frankenstein saga.

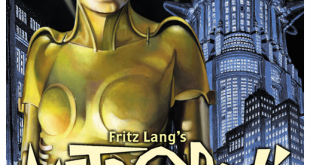

One of the brightest lights in German cinema was director Fritz Lang whose early serial adventure The Spiders (1919 and 1920) demonstrated a flair for combining popular entertainment and expressionist art. He continued his wining streak with the staggeringly popular Dr. Mabuse (1922) films. His silent film career culminated with the classic science fiction epic Metropolis (1927), which managed to be a groundbreaking classic and a financial flop—nobody’s perfect.

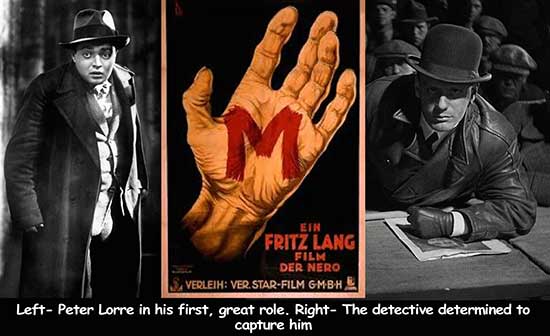

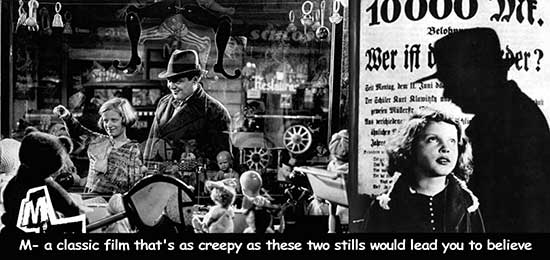

In 1931, he directed his first sound film entitled M, the tale of a murderous psychopath preying on children. It was a strange choice, first and foremost for its controversial subject matter. Fortunately the director still had enough industry ‘juice’ to get it financed. Lang announced his upcoming production under the working title Murderers Among Us only to be barred from Staaken Studios, where he’d shot Metropolis. He discovered that the studio head, a member of the up-and-coming Nazi party, instantly assumed that the film’s title referred to his goose stepping playmates. Eventually he relented and Lang was permitted to use the studio.

Lang eschewed big stars, instead casting a struggling stage actor named Peter Lorre to play cinema’s first serial killer. Lorre’s unforgettable performance launched him into European stardom. But his acclaim back home in Germany didn’t last long, and in 1933 the Jewish actor fled to Paris, barely escaping the Nazis. Shortly after arriving Lorre was snapped up by director Alfred Hitchcock for 1934’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, marking the beginning of a long and fruitful Hollywood career.

M was a pioneering film both artistically and technically. It was the first film to portray a murderer as something more than a one-dimensional villain. M’s serial killer is a man, flesh and blood, that’s unable control his savage impulses. In a particularly strong scene Lorre pleads for his life, stating, “I cannot help myself! I have no control over this evil thing that is inside me—the fire, the voices, the torment!” This newfound ‘sympathy for the devil’ struck a chord with audiences who’d never seen a truly human monster on screen before.

It probably helped that all the child murders take place off-screen, cleverly suggested rather than shown. To accomplish this Lang incorporated the visual flair that had made his silent movies so memorable, including massive crane shots, forced perspective and optical montages. This is especially remarkable as early sound films were still barely able to move the camera without destroying the precious dialogue. Hollywood was still locking cameras (and cameramen) in unventilated, soundproof steel boxes to muffle their noise. M’s camerawork is far more nimble than that year’s Hollywood horror blockbuster Dracula (1931).

Not content to just tell the story visually, Lang experimented with sound effects, utilizing multiple audio tracks, shocking sound effects and other tricks that would become hallmarks of cinematic suspense. This is particularly impressive considering that sound had only come on the movie scene in 1927 and was an entirely new process for European filmmakers. M was even the first film to tie a piece of music to a character; in this case Lorre’s whistling Hall of the Mountain King before each killing.

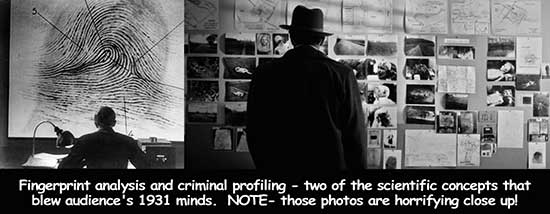

Along with being the first serial killer film M also invented the genre commonly known as ‘The Police Procedural’. Lang’s hero, Inspector Karl Lohmann, is a brilliant detective utilizing the cutting edge science of fingerprinting and handwriting analysis to track down the killer. The science on display in M was so new and exciting to audiences that afterwards they couldn’t get enough high tech crime stories. That enthusiasm has never waned and all nine thousand episodes of CSI secretly owe their existence to M.

All these elements helped make M a huge hit. But its popularity also stemmed from the German public’s fascination with mass murderers—today known as serial killers—that were sprouting like dandelions across the country.

Weimar Berlin was a depressing place with massive unemployment and constant food shortages. This led newspapers to search for stories to take the public’s mind off their empty bellies. The rising crop of serial killers was perfect fodder, but, unlike today’s media, the Weimar press didn’t need to exaggerate the barbarity of their crimes. Trust me, contemporary serial killers can’t hold a candle to the Weimar renaissance of human monsters. We’re talking vampires, cannibals, rapists, arsonists and pedophiles—with a few checking the box marked “all of the above.” But the real question is why did this happen?

You might be thinking that the horrors of WW1 created a legion of crazed veterans—bitter men, twisted by the brutality of war, putting their trench knifing skills to use on Berlin’s dirty boulevards. That might make a good movie script, but the reality was very different.

Let’s look at some statistics. According to criminal psychologists, the average serial killer starts their career between the ages of twenty-five and twenty-seven, precisely the age when most German males were drafted. Of the 11,000,000 German men sent to war over 6,000,000 were killed or seriously wounded (take a second to ponder that catastrophic number). That casualty rate alone should have thinned the Teutonic herd of potential serial murderers.

In truth a staggering ZERO percent of the era’s killers were scarred by The Great War’s battlefield horrors. Most avoided military service or deserted from the army before seeing a shot fired. Some actually profited from the conflict by selling black market meat. We’ll get to the source of that meat later. This certainly blows a hole in Hollywood’s “crazed veteran” stereotype.

So let’s get to the rogues’ gallery of draft dodging human monsters.

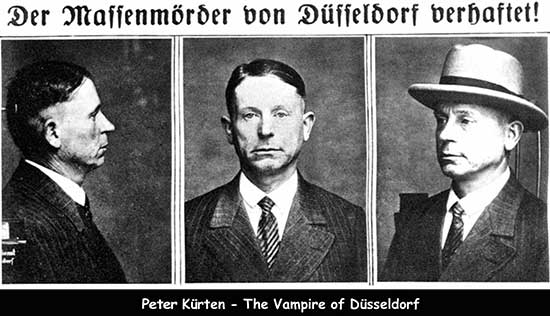

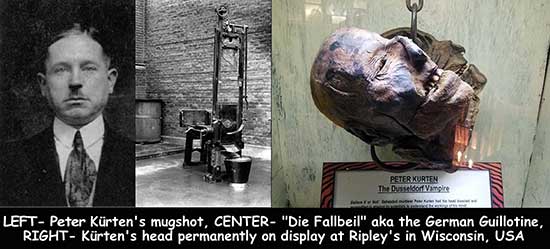

M’s most obvious inspiration was Peter Kürten, a murderous sexual predator who killed at least nine victims and attempted to murder thirty-one others between 1913 and 1917. He earned the nickname The Vampire of Dusseldorf for his habit of biting victims and drinking their blood.

Kürten checked off all the boxes that modern profilers use to classify serial killers— a brutal father who sexually abused his children, a youthful period of torturing animals, and drifting into petty crime to earn his keep.

Kürten claimed to have committed his first murders at age nine when he drowned two of his playmates—deaths that had been deemed accidental until his confession. From that point on his life was a hellish cavalcade of bestiality (literally—dogs, sheep, a swan, you name it), arson, rape, and, beginning in 1913, murder. His first victim was ten-year-old Christine Klein who he sexually assaulted and stabbed to death in her home while her parents operated a pub downstairs.

He would have killed more if he hadn’t been stuck in prison from 1914 to 1921 for deserting the army. Upon his release Kürten married a former prostitute and, for the next eight years, attempted to live a normal existence. But in February of 1929, he went off the rails, murdering eight people while suspected of killing dozens more. Kürten’s ‘vampire’ nickname was well earned, as he drank the blood of his victims whenever circumstance allowed. This blood drinking would excite him into an involuntary orgasm.

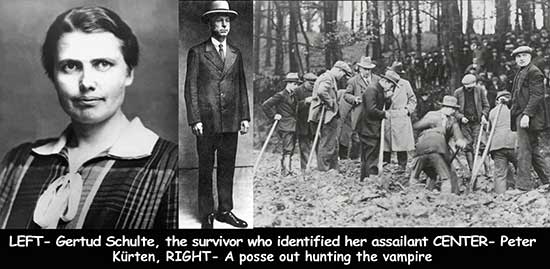

On top of the murders he assaulted and stabbed dozens of women who survived. The newspapers went bananas, using terms like vampire and monster to describe the mysterious maniac on the loose. Kürten genuinely enjoyed the publicity his exploits received and even contacted newspapers to inform them of where victims’ bodies could be found. Eventually a survivor identified Kürten, but he still managed to elude the police.

He then concocted a plan to let his wife turn him in and collect the substantial reward. She did. Unfortunately Kürten confessed their plan and she was deemed ineligible to collect. In 1931, Kürten confessed to nine murders, which, for the woefully undermanned police department, was enough. Kürten was convicted and sentenced to execution by Die Fallbeill—the German version of the guillotine. This left dozens of murders and assaults he was suspected of unsolved.

On the morning of his execution, he asked the prison doctor, “Tell me, after my head has been chopped off will I still be able to hear, at least for a moment, my own blood gushing from the stump of my neck?” When told that his ears and brain would probably function for a few moments, he replied, “That would be the pleasure to end all pleasures.” He got that final thrill, closing the book on his murderous career.

In a macabre postscript, a Norwegian antique dealer named Arne Coward purchased Kürten’s mummified head in 1946. Coward took the newly acquired noggin to Waikiki, Hawaii, where it became part of his extensive collection of torture devices. Upon Coward’s death his collection was auctioned off to Ripley Entertainment Inc. who put the mummified head on display at their Wisconsin Dells Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Museum. So next time you’re in the Badger State and want to traumatize the kids stop by Ripley’s. The vampire awaits you.

Fritz Lang considered M to be his finest work, but adamantly denied basing his killer on Peter Kürten. In an interview he stated, “At the time I decided to use the subject matter of M, there were many serial killers terrorizing Germany—Haarmann, Grossman, Kürten and Denke.” Lang wasn’t exaggerating; the place was crawling with maniacs. In part two we’ll look at those horrific serial killers and Detective Ernst Gennat, the Buddha of Criminologists who brought them all to justice. He did it by inventing the science of criminal profiling, even coining the term serial killer in the process. Be sure to check it out because, to quote homegrown maniac Jeffrey Dahmer, “That’s when the cannibalism started.”

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews