Jay McRoy: author- Interview – 12.09.08

Jay McRoy: author- Interview – 12.09.08

Author Jay McRoy stopped by answer some questions about his books and shed a little light on Asian horror cinema! Check it out!

Japanese Horror Cinema, Nightmare Japan : Contemporary Japanese Horror Cinema, and Monstrous Adaptations: Generic and Thematic Mutation in the Horror Film,are your latest books, can you tell us about them?

Jese Horror CinemEdinburgh University Press & University of Hawaii Press, 2005) is an anthology of essays that examines the genre’s dominant aesthetic, cultural, political, and technological underpinnings. Individual chapters address key topics such as: the debt Japanese horror films owe to various Japanese theatrical and literary traditions; the popular “avenging spirit” motif; the impact of atomic warfare, rapid industrialization and apocalyptic rhetoric on Japanese visual culture; the extents to which changes in the economic and social climate inform representations of monstrosity and gender; the influence of recent shifts in audience demographics; and the developing relations and contestations between Japanese and Western (Anglo-American and European) horror film tropes and traditions. I was delighted to have an enthusiastic line-up of top-notch contributors, including Christopher Bolton, Phillip Brophy, Ian Conrich, Gareth Evans, Ruth Goldberg, Richard Hand, Steffen Hantke, Matt Hills, Frank Lafond, Graham Lewis, Gary Needham, Steven Jay Schneider, Christopher Sharrett, Eric White, and Tony Williams.

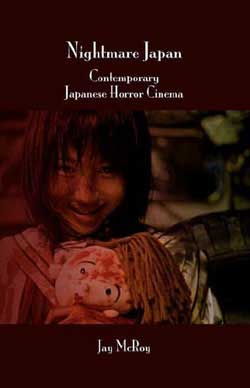

In my solo-authored book Nightmare Japan: Contemporary Japanese Horror Cinema (Rodopi, 2007), I explore how important and innovative works of cinematic horror by directors like Tsukamoto Shinya, Sato Hisayasu, Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Nakata Hideo, and Miike Takashi revisit and redefine the horror genre in both its Japanese and global contexts. In the process, I argue that contemporary Japanese horror film contributes exciting new visions, from postmodern re-workings of traditional avenging spirit narratives to groundbreaking forays into cinematic terror that position representations of radical or ‘monstrous’ embodiment as metaphors for larger socio-political concerns, from shifting gender roles and reconsiderations of the importance of the extended family as a social institution, to reconceptualisations of the very notion of cultural and national boundaries.

With Monstrous Adaptations: Generic and Thematic Mutation in the Horror Film (Manchester University Press, 2007), I collaborated with film and theater scholar Richard Hand. Together, we compiled an anthology of essays that address the concept of adaptation in relation to horror cinema. This proved to be an exciting project for us, as adaptation is not only a key cultural practice and strategy for filmmakers, but it is also a crucial recurring theme within horror cinema as a whole. Horror film’s history is, of course, full of adaptations that have drawn from fiction or folklore, or that have assumed the shape of remakes of pre-existing films, and the horror genre itself abounds with its own myriad transformations and transmutations. Again I was lucky enough to work with a terrific collection of film critics, including: Linnie Blake, Brigid Cherry, Guy Crucianelli, Ruth Goldberg, Steffen Hantke, Reynold Humphries, I.Q. Hunter, Mikel Koven, Julian Petley,

Murray Pomerance, and Marianne Shaneen.

Where can we find your books?

They are available through many online merchants (including, of course, major retailers like www.amazon.com and www.bn.com). The books can also be purchased directly from the publisher.

Where did the idea to write about Japanese horror come from? Who or what inspired it?

The inspiration sprung from curiosity. I wanted to know more and more about the cultural and artistic traditions that informed these films.

Had you been working in the horror field prior to putting together your amazing books?

Since childhood I have been drawn to macabre subjects, so as I became increasingly interested in literature and cinema, it seemed only natural that horror was the genre to which I repeatedly gravitated. When it came time to write my Ph.D. dissertation, I focused extensively on depictions of splattered bodies in horror film. I’ve found that a person can learn a lot about the world by studying what people fear: the ideas or images coded as “monstrous” or “abject.”

How long have you been interested in Asian horror?

How long have you been interested in Asian horror?

A. My initial introduction to Asian horror cinema occurred when I was in high school and saw Mizoguchi Kenji’s Ugetsu (1954) and Shindô Kaneto’s Onibaba (1965). Although the prints I viewed were worn and the subtitles difficult to read, I remember being struck by how radically the tone of these works differed from the “giant monster” films that a local television station played every Saturday afternoon.. Ugetsu and Onibaba were creepy, but they were also heart-breakingly poignant in ways that I registered emotionally but did not yet possess the vocabulary or critical savvy to articulate.

Why does Asian horror seem to strike more of a punch than American horror?

I don’t know if they “strike more of a punch” as much as they strike out or confront viewers in ways that, say, fans of North American horror films see as unfamiliar or uncanny. For example, ghosts in Asian horror films are generally depicted more sympathetically than in US horror films. Also, many Asian horror films generate suspense and dread by what they don’t show, or what the directors parcel out methodically, often relegating the object of dread to the borders of the frame or allowing us only partial, fleeting glimpses. Such an approach – more of a slow burn than a series of explosions – was seen as a welcome departure for North American audiences burned out on slasher film sequels. This is not to say that Asian horror films shun blood and gore; the Guinea Pig movies contain some of the most extreme representations of physical violence in all of world cinema. The actor Charlie Sheen, mistakenly thinking he had stumbled upon snuff

footage, even turned a VHS recording of one of the Guinea Pig films to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Why do you think Asian horror has just recently become noticed in America?

Certainly, the ever-increasing resources offered by the Internet played a huge role. As horror fans from around the globe were able to network more easily, their mutual horizons expanded. DVDs from studios around the globe could suddenly be obtained with a few keystrokes and a credit card.

What’s some of your personal favorite contemporary Asian horror films? Do you have any favorite Asian Horror director(s)?

I have a particular fondness for the films of Tsukamoto Shinya, especially Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), Vital (2004), and Haze (2005). Shimizu Takashi’s Marebito (2004) was an exciting departure from his Ju-on films, and Kurosawa Kiyoshi is a master when it comes to evoking dread. Sono Sion rarely disappoints; Noriko’s Dinner Table (2005) is one of my favorite films, as is his Suicide Club (2002).

Oxide Pang’s Ab-Normal Beauty (2004) is at once beautiful and brutal, Kim Ji-woon’s A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) is a classic merger of Western and Korean Gothic sensibilities, and Fruit Chan’s Dumplings (2004) never fails to whet my appetite for corporeal destruction.

J- Horror or K- Horror?

A. Each tradition has its own dark charms. And don’t overlook horror cinema from Hong Kong, Thailand, and the Philippines.

A. I have essays forthcoming in several anthologies. Among these writings are extended analyses of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez’s Death Proof (2007) and Thomas Clay’s The Great Ecstasy of Robert Carmichael (2005). I am also experimenting with electronic cinema, which I find to be an exciting medium and an opportunity for me to express myself in a creative, rather than exclusively critical, way.

Any departing words for our fellow Asian Horror lovers?

Keep watching and never hesitate to investigate the works of emerging directors from around the globe. For example, there is some terrific nightmare fuel spilling out of France – see, if you can, Julien Maury and Alexandre Bustillo’s À l’intérieur (2008), Fabrice du Welz’s Calvaire (2004), David Moreau and Xavier Palud’s Ils (2006), Xavier Gens’ Frontièr(s) (2007), and Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs (2008).

Thanks so much for stopping by Jay! We look forward to reading more form you in the future!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews