SYNOPSIS:

Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí present seventeen minutes of bizarre, surreal imagery.

REVIEW:

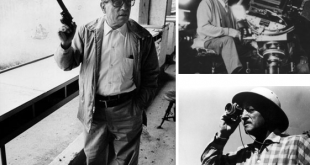

Luis Bunuel is widely considered the father of surreal cinema. Salvador Dali is arguably one of the best known artists in the history of painting, a medium he also took into the world of surrealism. Put them together, and you end up with one of the strangest, most interesting, most widely praised films of all time, even still today, nearly 90 years after its release. Un Chien Andalou is the film that you’ve no doubt seen at least parts of, whether in an intro to film class or in a collage of cinema’s most disturbing scenes. It’s a film that was born of the literal dreams of the writer and director, a film that the director was allegedly so convinced would confuse the opening night audience to the point of anger that he hid behind the screen armed with rocks, a film that has such a wide variety of in depth, intelligent, well-constructed interpretations and might just mean absolutely nothing at all.

Un Chien Andalou (translated to English, An Andalusian Dog) opens with a legendary scene – a man sharpens his straight razor, then while watching a line of clouds cut across the moon, he slices a woman’s eye open (and yes, there really is an eye cut open, but it is that of a dead cow – also of note, the image of clouds cutting across the moon was right out of a dream of director Bunuel’s). From there, we cut to 8 years later, and a man is carrying a box across town on his bicycle. From her window, a woman sees him fall and goes down to check on him.

He is hurt badly, possibly dead, and so she takes the box he is carrying and brings it to her apartment, where she lays clothing out on the bed and seems to will it to life. A different man (or the same man?) is also in her apartment, and he is watching ants crawl out of a hole in his hand (and this was from writer Dali’s dream). We then see a crowd gather around a severed hand on the ground, which a cop picks up and places inside what appears to be the same box as before and hands it to a woman who is then hit by a car, none of which makes anything in this movie any easier to understand.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be looking for meaning. It is said that Bunuel made Un Chien Andalou as a direct attack on intellectuals and avant garde cinema of the time, intending to offend and shock them.

While writing the film, Bunuel and Dali made certain to not include anything that had a rational explanation, and have pointed out that there is no symbolism at play anywhere in the 16 or so minute runtime. So perhaps we should just appreciate what is on screen and how it is presented to us. There a constant dream-like feel throughout, much like what David Lynch does in his films – we are presented with scenes that almost make sense, except for one or two details that would seem minor if not for the absurdity of it all. Add in the non-linear timeline and the imagery that goes beyond dream logic, and we are left with a story-less story that draws us in and holds us to the end.

Obviously Un Chien Andalou is a highly influential film, not only because it kicked off the career of Bunuel as one of the top directors of his time. This film also helped establish surrealism as a form of cinema, somehow succeeding even as its creators assumed/hoped it wouldn’t. Thanks to things like Un Chien Andalou, we now have the films of David Lynch, and Alejandro Jodorowsky, and Fernando Arrabal, and so many others.

And despite it “not meaning anything,” it is still a highly enjoyable film. Highly recommended, of course, to anyone, horror fan or not, who can appreciate good filmmaking, not just because of its history, and not just because we are supposed to, but because it still stands, all these years later, as a well made film.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews