SYNOPSIS:

“This version of Dracula is closely based on Bram Stoker’s classic novel of the same name. A young lawyer (Jonathan Harker) is assigned to a gloomy village in the mists of eastern Europe. He is captured and imprisoned by the undead vampire Dracula, who travels to London, inspired by a photograph of Harker’s betrothed, Mina Murray. In Britain, Dracula begins a reign of seduction and terror, draining the life from Mina’s closest friend, Lucy Westenra. Lucy’s friends gather together to try to drive Dracula away.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Transformed over the decades by directors as diverse as Tod Browning, Terrence Fisher, John Badham and Paul Morrissey, Bram Stoker‘s iconic Transylvanian finally fell into the hands of a so-called master filmmaker in 1992. Francis Ford Coppola began with Roger Corman‘s low budget B-graders in the sixties, soon declared a movie genius during the seventies, moved into mad megalomania during the eighties and, by the nineties, was considered by many to be just plain mad. Having overcome his Cecil B. DeMille complex (now afflicting James Cameron), Coppola still wants to make expensive movies but, at this stage of his career, has completely run out of original ideas, hence his 2001 redux re-release of Apocalypse Now (1979). Adopting an avant garde approach of ingenious dissolves (a peac**k feather becomes a railway tunnel) and simplistic visual trickery (shadowplay and puppets), combined with a rampant Gothic aesthetic, Coppola promised the godfather of all vampire films.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), simply titled Dracula in some countries, features the sartorial spectacle of Eiko Ishioka‘s costumes, Wojcieh Kilar‘s lush soundtrack music and a portentous atmosphere that’s almost palpable but, even when equipped with a reliable road map, compass and crew, Coppola once again finds himself up a river without a paddle. Quite simply, Bram Stoker’s Dracula may well be the longest two hours lavishly devoted to sexual symbolism, bestiality, necrophilia, dodgy transitions, ludicrous acting and atrociously bad hair. The end result is a prime example of a film that is far less than the sum of its parts. With an armoury of cinematic artifice at his disposal, Coppola struggles to conduct this sumptuous symphony of the macabre with consummate grace, teasing and tantalising with artful eroticism, shocking with bestial transformations, and astonishing with numerous subtle flourishes, like when the roses wither in the vampire’s wake.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), simply titled Dracula in some countries, features the sartorial spectacle of Eiko Ishioka‘s costumes, Wojcieh Kilar‘s lush soundtrack music and a portentous atmosphere that’s almost palpable but, even when equipped with a reliable road map, compass and crew, Coppola once again finds himself up a river without a paddle. Quite simply, Bram Stoker’s Dracula may well be the longest two hours lavishly devoted to sexual symbolism, bestiality, necrophilia, dodgy transitions, ludicrous acting and atrociously bad hair. The end result is a prime example of a film that is far less than the sum of its parts. With an armoury of cinematic artifice at his disposal, Coppola struggles to conduct this sumptuous symphony of the macabre with consummate grace, teasing and tantalising with artful eroticism, shocking with bestial transformations, and astonishing with numerous subtle flourishes, like when the roses wither in the vampire’s wake.

It was actress Winona Ryder who initially brought James V. Hart‘s script to the attention of Coppola, who was attracted to the sensual elements of the screenplay and wanted the movie to resemble an erotic dream. Due to delays and cost overruns on some of his previous projects, Coppola was determined to bring this film in on time and on budget. To accomplish this he filmed on sound stages to avoid potential troubles caused by bad weather. He also chose to invest a significant amount of the budget into costumes in order to showcase the actors which he considered the jewels of the feature. He had an artist storyboard the entire film in advance to carefully illustrate each planned shot, a process which created around a thousand images. He turned the drawings into a choppy animated film and added music, then spliced in scenes from Jean Cocteau‘s Beauty And The Beast (1946) along with paintings by Gustav Klimt and other symbolist artists. Coppola showed the animated film to his designers to give them an idea of the mood and theme he was aiming for, and demanded weird non-formula designs: “Give me something that either comes from the research or that comes from your own nightmares! I gave them paintings and drawings, and I talked to them about how I thought the imagery could work.”

It was actress Winona Ryder who initially brought James V. Hart‘s script to the attention of Coppola, who was attracted to the sensual elements of the screenplay and wanted the movie to resemble an erotic dream. Due to delays and cost overruns on some of his previous projects, Coppola was determined to bring this film in on time and on budget. To accomplish this he filmed on sound stages to avoid potential troubles caused by bad weather. He also chose to invest a significant amount of the budget into costumes in order to showcase the actors which he considered the jewels of the feature. He had an artist storyboard the entire film in advance to carefully illustrate each planned shot, a process which created around a thousand images. He turned the drawings into a choppy animated film and added music, then spliced in scenes from Jean Cocteau‘s Beauty And The Beast (1946) along with paintings by Gustav Klimt and other symbolist artists. Coppola showed the animated film to his designers to give them an idea of the mood and theme he was aiming for, and demanded weird non-formula designs: “Give me something that either comes from the research or that comes from your own nightmares! I gave them paintings and drawings, and I talked to them about how I thought the imagery could work.”

Coppola was insistent that he did not want to use any kind of computer-generated imagery when making the movie, wishing instead to use practical in-camera effects techniques appropriate to the film’s period setting. He initially hired a standard visual effects team, but when they told him that the things he wanted to achieve were impossible without using modern digital technology, Coppola fired them and hired his 29-year-old son Roman Coppola. As a result, all of the visual effects seen in the film were achieved without the use of optical or computer-generated effects. Any sequences that would have typically required the use of compositing were instead achieved by either rear-projection or through multiple exposures, all the while using matting to ensure that only the desired areas of film were exposed. Forced perspective was often employed to combine miniatures or matte paintings with full-sized elements, or create distorted views of reality, such as holding the camera upside down or at odd angles to create the effect of objects defying the laws of physics.

Coppola was insistent that he did not want to use any kind of computer-generated imagery when making the movie, wishing instead to use practical in-camera effects techniques appropriate to the film’s period setting. He initially hired a standard visual effects team, but when they told him that the things he wanted to achieve were impossible without using modern digital technology, Coppola fired them and hired his 29-year-old son Roman Coppola. As a result, all of the visual effects seen in the film were achieved without the use of optical or computer-generated effects. Any sequences that would have typically required the use of compositing were instead achieved by either rear-projection or through multiple exposures, all the while using matting to ensure that only the desired areas of film were exposed. Forced perspective was often employed to combine miniatures or matte paintings with full-sized elements, or create distorted views of reality, such as holding the camera upside down or at odd angles to create the effect of objects defying the laws of physics.

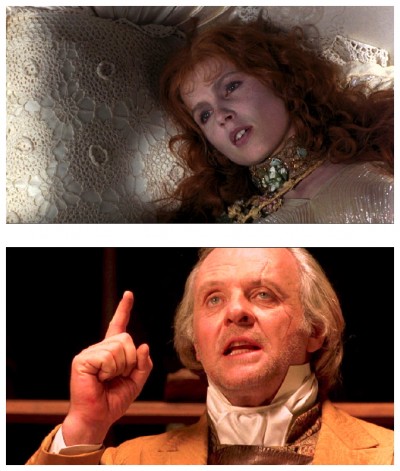

Lacking the suavity of Christopher Lee and the impish malevolence of Bela Lugosi, Gary Oldman‘s understated performance remains unique in the annals of screen Draculas, investing the Count with a piety that almost seeks to transcend his monstrous nature. Dressed in what looks like a lobster suit for battle, Oldman later has his hair blow-dried like Tom Hulce in Amadeus (1984), making him one of the biggest fashion guinea pigs in the film industry since Cher. In fact, Coppola’s version largely paints this vampire as a tragic figure, a sentiment echoed by Sadie Frost‘s performance as the doomed Lucy. Baring nascent fangs while resplendent in a frill-necked bridal gown and cradling the innocent child that is her next victim, this potent image personifies the very horror at the heart of the vampire myth – beauty and the beast.

Lacking the suavity of Christopher Lee and the impish malevolence of Bela Lugosi, Gary Oldman‘s understated performance remains unique in the annals of screen Draculas, investing the Count with a piety that almost seeks to transcend his monstrous nature. Dressed in what looks like a lobster suit for battle, Oldman later has his hair blow-dried like Tom Hulce in Amadeus (1984), making him one of the biggest fashion guinea pigs in the film industry since Cher. In fact, Coppola’s version largely paints this vampire as a tragic figure, a sentiment echoed by Sadie Frost‘s performance as the doomed Lucy. Baring nascent fangs while resplendent in a frill-necked bridal gown and cradling the innocent child that is her next victim, this potent image personifies the very horror at the heart of the vampire myth – beauty and the beast.

As Oldman flounders about in a range of hideous disguises, he still fails to upstage Sir Anthony Hopkins, who looks like he’s impersonating Peter Sellers from The Pink Panther (1963) movies. Sir Anthony tries too hard to live-up to his reputation as living heir to Laurence Olivier (who coincidentally played the role in John Badham‘s languid 1979 version). That being said, as the world-weary vampire slayer, Hopkins’ unrestrained portrayal and delivery of words such as “Dracul!” and “Nosferatu!” resonates with a conviction lesser actors cannot hope to master. Thankfully Oldman, Frost and Hopkins – together with the inspired casting of Tom Waits as the bug-munching Renfield – does much to distract from the insipid contributions from Winona Ryder and Keanu Reeves. Before she was stealing clothes, Winona was stealing Gary Oldman’s heart, an easy alternative when considering her other option: cold fish Keanu. In Keanu’s defense I have to admit that Jonathan Harker has always been one of the lamest male characters in cinematic history.

As Oldman flounders about in a range of hideous disguises, he still fails to upstage Sir Anthony Hopkins, who looks like he’s impersonating Peter Sellers from The Pink Panther (1963) movies. Sir Anthony tries too hard to live-up to his reputation as living heir to Laurence Olivier (who coincidentally played the role in John Badham‘s languid 1979 version). That being said, as the world-weary vampire slayer, Hopkins’ unrestrained portrayal and delivery of words such as “Dracul!” and “Nosferatu!” resonates with a conviction lesser actors cannot hope to master. Thankfully Oldman, Frost and Hopkins – together with the inspired casting of Tom Waits as the bug-munching Renfield – does much to distract from the insipid contributions from Winona Ryder and Keanu Reeves. Before she was stealing clothes, Winona was stealing Gary Oldman’s heart, an easy alternative when considering her other option: cold fish Keanu. In Keanu’s defense I have to admit that Jonathan Harker has always been one of the lamest male characters in cinematic history.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula received generally positive reviews from critics like Vincent Canby, who described the film as having been created with the enthusiasm of a precocious film student who has magically acquired a master’s command of his craft, and Richard Corliss stated that, “Coppola brings the old spook story alive. Everyone knows that Dracula has a heart – Coppola knows that it is more than an organ to drive a stake into. To the director, the Count is a restless spirit who has been condemned for too many years to interment in cruddy movies. This luscious film restores the creature’s nobility and gives him peace.” The late great Roger Ebert admitted that, “I enjoyed the movie simply for the way it looked and felt. Production designers Dante Ferretti and Thomas Sanders have outdone themselves. The cinematographer Michael Ballhouse gets into the spirit so completely he always seems to light with shadows.”

Bram Stoker’s Dracula received generally positive reviews from critics like Vincent Canby, who described the film as having been created with the enthusiasm of a precocious film student who has magically acquired a master’s command of his craft, and Richard Corliss stated that, “Coppola brings the old spook story alive. Everyone knows that Dracula has a heart – Coppola knows that it is more than an organ to drive a stake into. To the director, the Count is a restless spirit who has been condemned for too many years to interment in cruddy movies. This luscious film restores the creature’s nobility and gives him peace.” The late great Roger Ebert admitted that, “I enjoyed the movie simply for the way it looked and felt. Production designers Dante Ferretti and Thomas Sanders have outdone themselves. The cinematographer Michael Ballhouse gets into the spirit so completely he always seems to light with shadows.”

The film was declared a box-office hit grossing more than US$215 million worldwide, making it the ninth highest-grossing film of 1992. Although legitimised with the ‘Bram Stoker’ prefix Coppola’s version is far from definitive, but it’s difficult to deny the artistic talents that went into creating this mesmerising reinvention of the classic tale. It’s vitally important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because an old gypsy woman told me that if you don’t read all my articles from now on, the entire world will be destroyed. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but she was just so certain, I feel we’d best not take the risk. So enjoy your week, and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

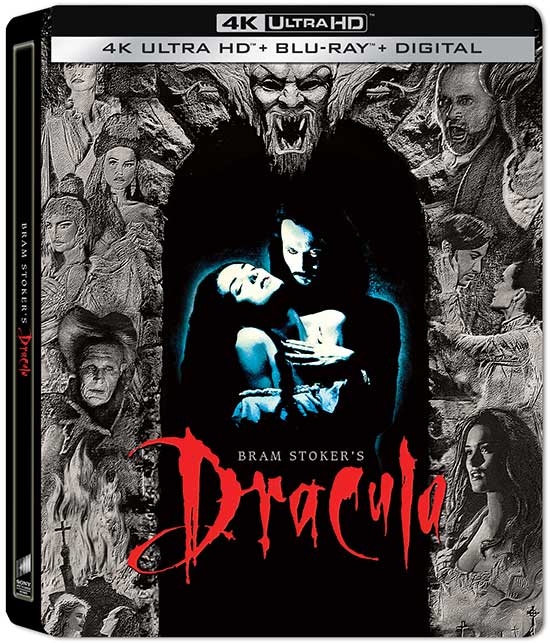

- Presented in full 4K resolution, now with Dolby Vision, plus immersive Dolby Atmos audio + 5.1 & 2.0 audio options

- In addition to hours of existing special features, now also includes the original music video and a rare 30-minute archival behind-the-scenes featurette

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) is now available on 4K Steelbook

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews