SYNOPSIS:

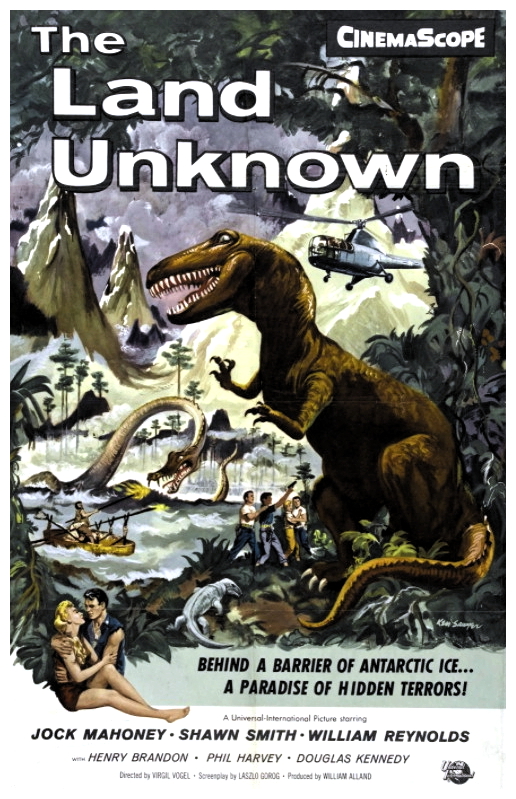

“Navy Commander Hal Roberts is assigned to lead an expedition to Little America in Antarctica to investigate reports of a mysterious warm water inland lake discovered a decade earlier. His helicopter and its small party, including beautiful reporter Maggie Hathaway, is forced down into a volcanic crater by a fierce storm. They find themselves trapped in a lush tropical environment that has survived from the Mesozoic Era. Fighting carnivorous plants, dinosaurs, and a limited time window, they struggle to survive and repair the helicopter, their only means of escape. They are both helped and hindered by Doctor Carl Hunter, a megalomaniac survivor of an earlier expedition, who has learned to adapt to the hostile environment.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

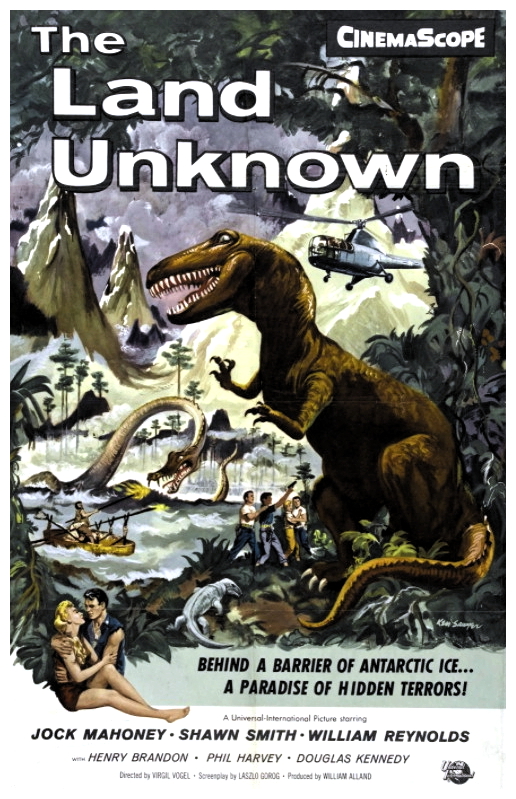

Famous for realistic television dramas like Centennial (1978), Skag (1980) and Portrait Of A Rebel: The Remarkable Mrs. Sanger (1980), Virgil Vogel began his directing career in the fifties at Universal when the studio was Hollywood’s great fantasy factory. Among the steady stream of science fiction movies produced during the fifties, Vogel’s The Mole People (1956) and The Land Unknown (1957) stand out as two of the most enjoyable journeys into fantastic scientific adventure. In The Mole People, Vogel took fantasy fans on a guided tour of a bizarre underground civilisation populated by a grotesque race of humanoids who could slither their way through the earth. In The Land Unknown, he led audiences into a savage prehistoric jungle nestled amidst the icy reaches of the South Pole. Vogel’s experience in the editing and effects of many of Universal’s previous science fiction features came in handy when making these strange worlds come alive within the confines of their meagre budgets.

The producer on both these pictures was William Alland, responsible for most of Universal’s science fiction movies of the decade, from It Came From Outer Space (1953) and Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954) to Tarantula (1955) and The Deadly Mantis (1957). Vogel knew Alland well from his editing days and it was through this friendship that he was able to make the transition to director. “William Alland, I think, was tops in his field as a science fiction producer. His basic theory was to take a scientific fact, then start leading the audience away from it in such a gentle way that they didn’t realise they were very far beyond it by the time the picture got going. If you base the premise of your fantasy film on fact, you kept the audience believing that everything else you tell them is also true.”

This approach served Alland well and its application was particularly apparent in the conception of the story for The Land Unknown. The scientific fact that this movie was based on was derived from a discovery made by the great explorer Admiral Richard E. Byrd. In 1947, Byrd found that in the middle of the frozen regions of the South Pole, there was a lake that always remained at eighty degrees fahrenheit (about 26 degrees celsius). From this fact it was assumed that the heat from the valley of this lake would rise up to the sub-zero air surrounding the area to produce a layer of fog thousands of metres across. With this fog bank to seal it off, the temperature on the floor of the valley would then remain constant and, if this were so, the heat pocket may have escaped the ice age. In other words, this valley would not have evolved past the Mesozoic era. Instead of modern biological conditions, the valley would be overrun with animal and plant life from a prehistoric age. And thus, from the single fact of the ‘warm lake’ in the Antarctic, Alland led the audience gently into a land of dinosaurs.

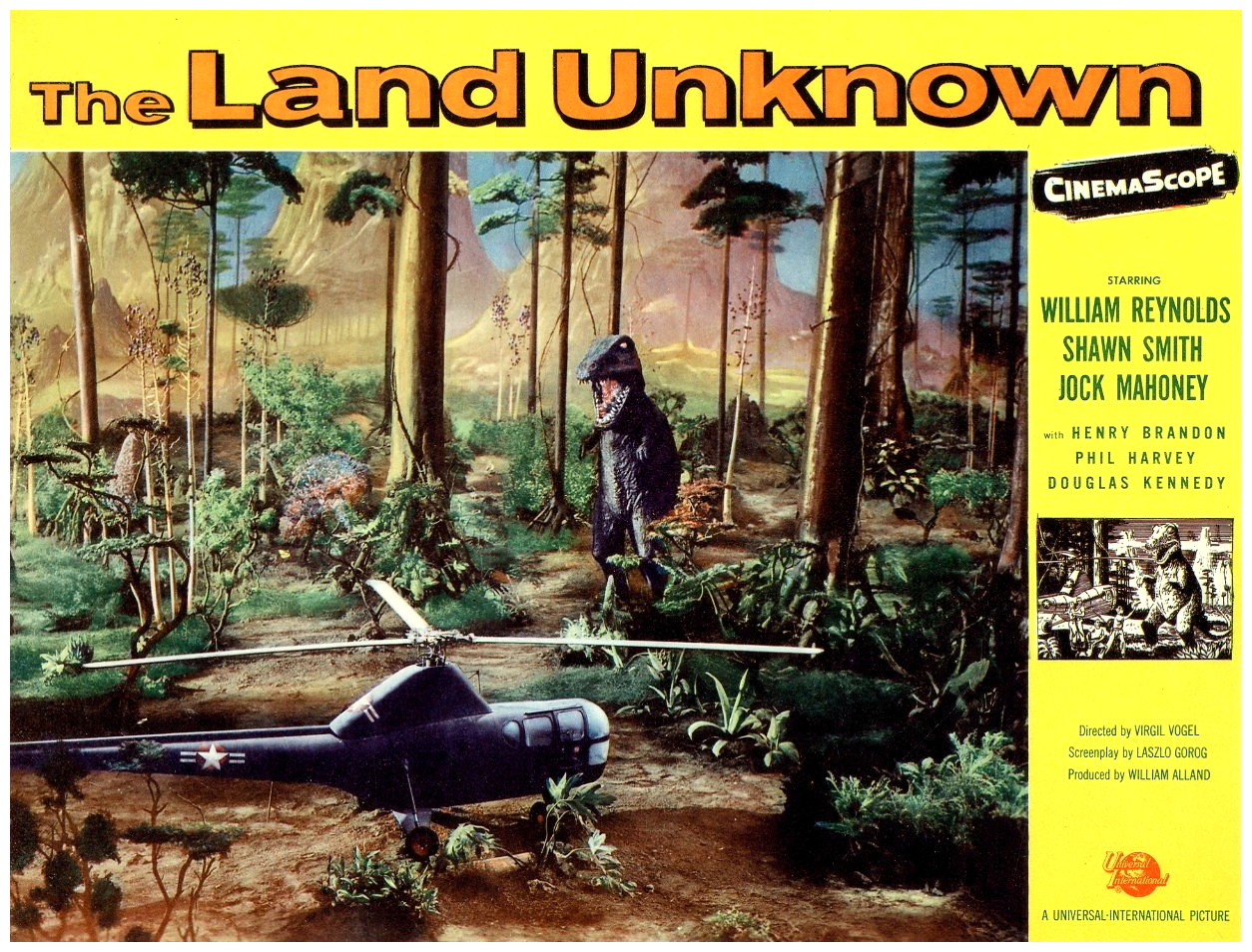

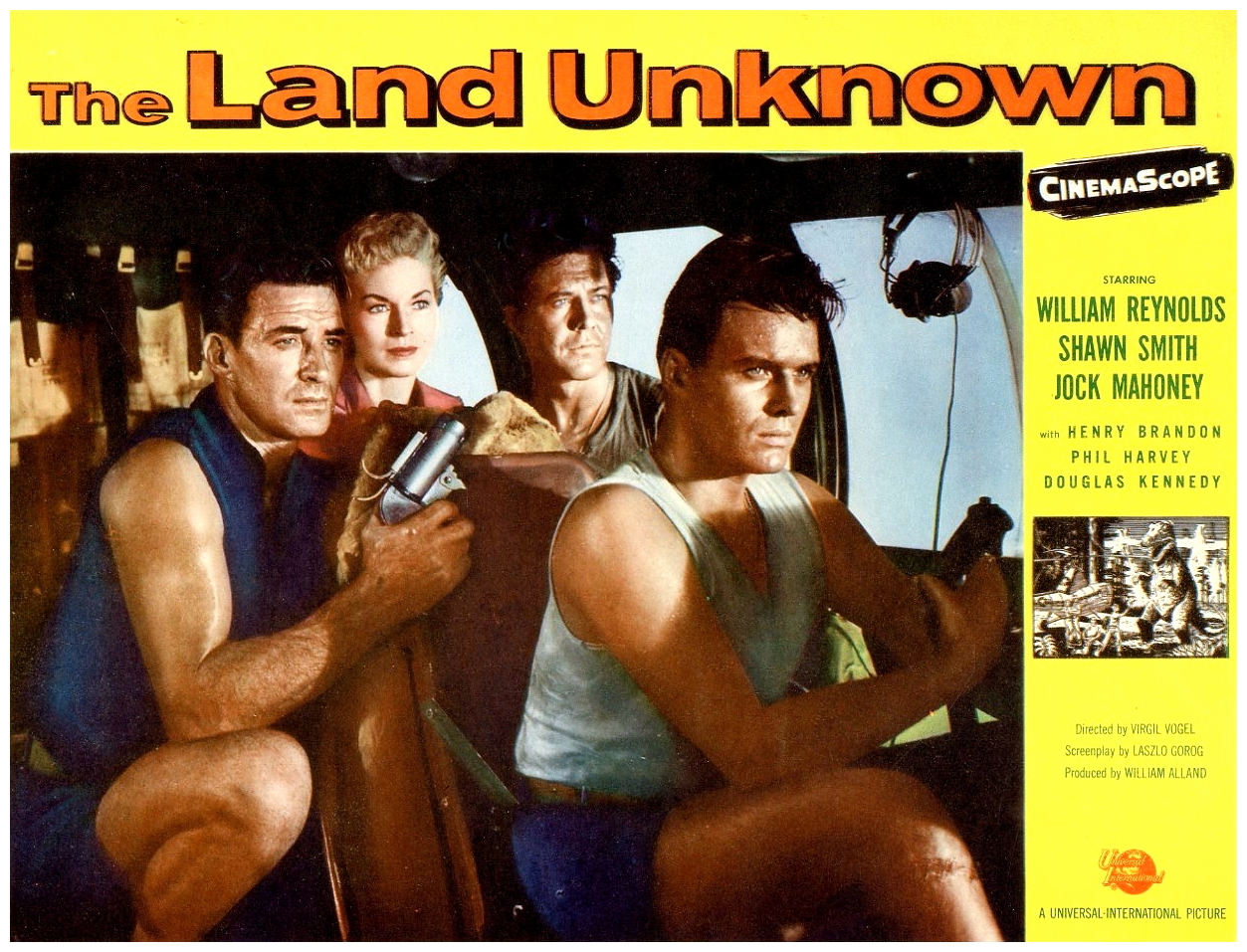

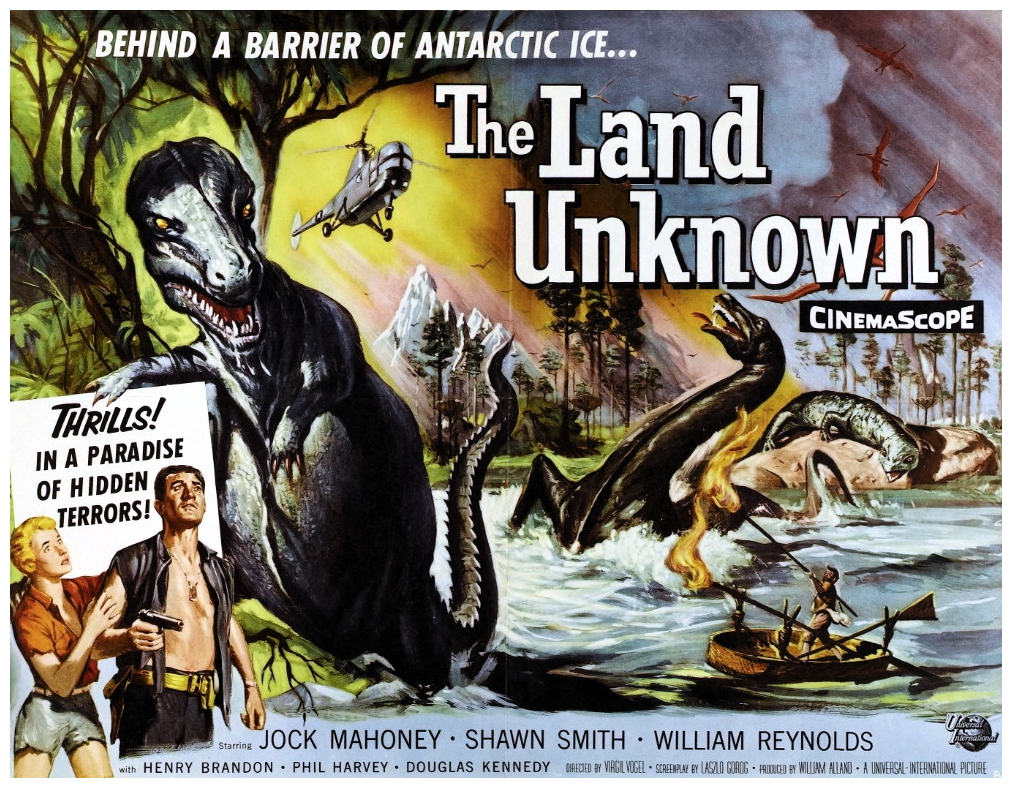

Alland’s theory of moving from fact to fact-based fiction was realised by starting with actual stock footage of the South Pole photographed by Admiral Byrd’s expedition and then progressing to artificially created scenes. Commander Hal Roberts (Jock Mahoney) is a naval officer in charge of a scientific expedition that is sent to investigate the inexplicably warm lake at the South Pole. Accompanying him is Navy scientist Lieutenant Jack Carmen (William Reynolds) and journalist Margaret Hathaway (Shawn Smith). They’re hovering above the lake in a helicopter (a Sikorsky S-51) when a storm strikes and forces them down into the thick layer of fog. Suddenly a prehistoric pterodactyl collides with the helicopter. The flying lizard escapes but the helicopter’s controls are jammed, and they have to make a crash landing in a deep chasm where they find themselves surrounded by a prehistoric jungle.

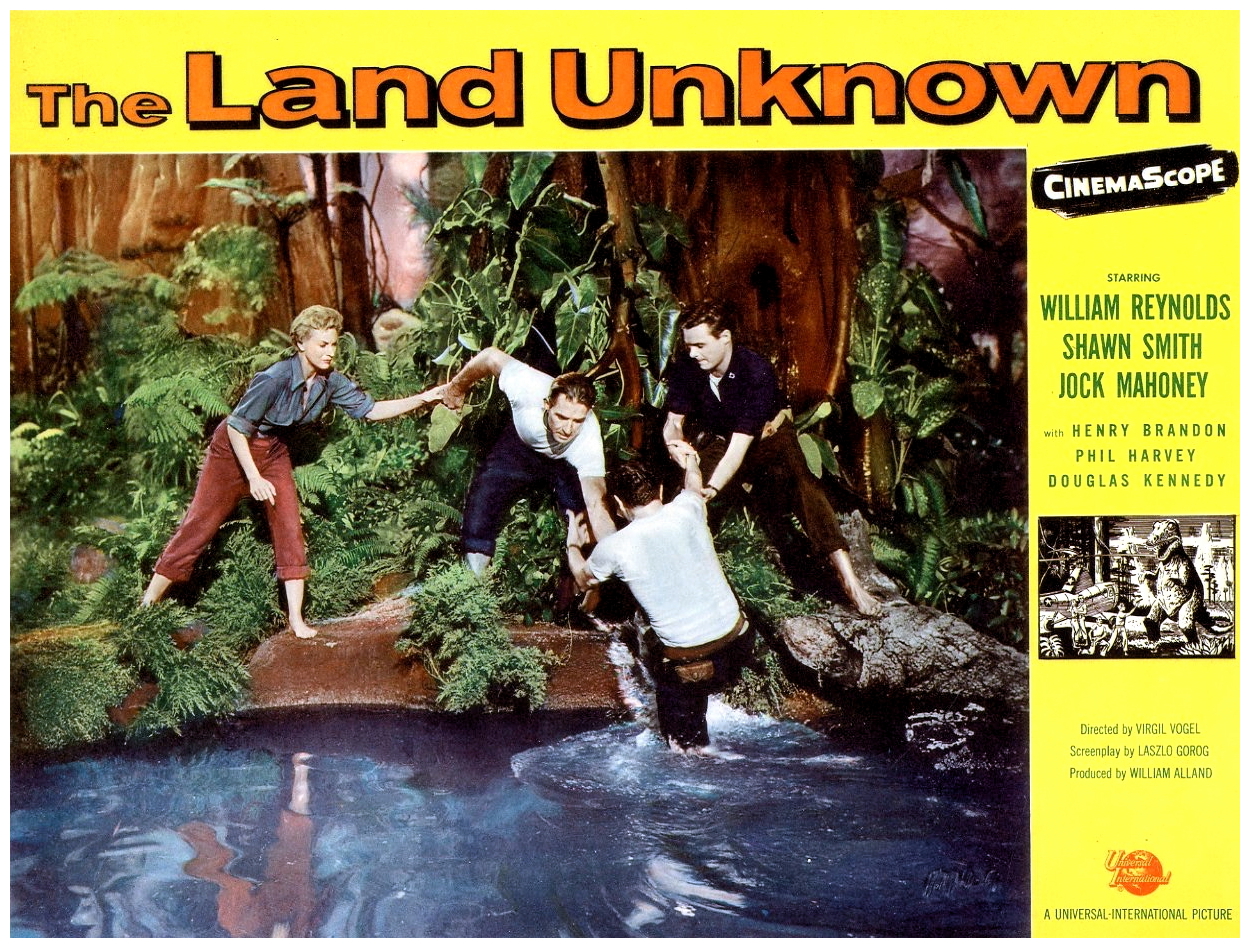

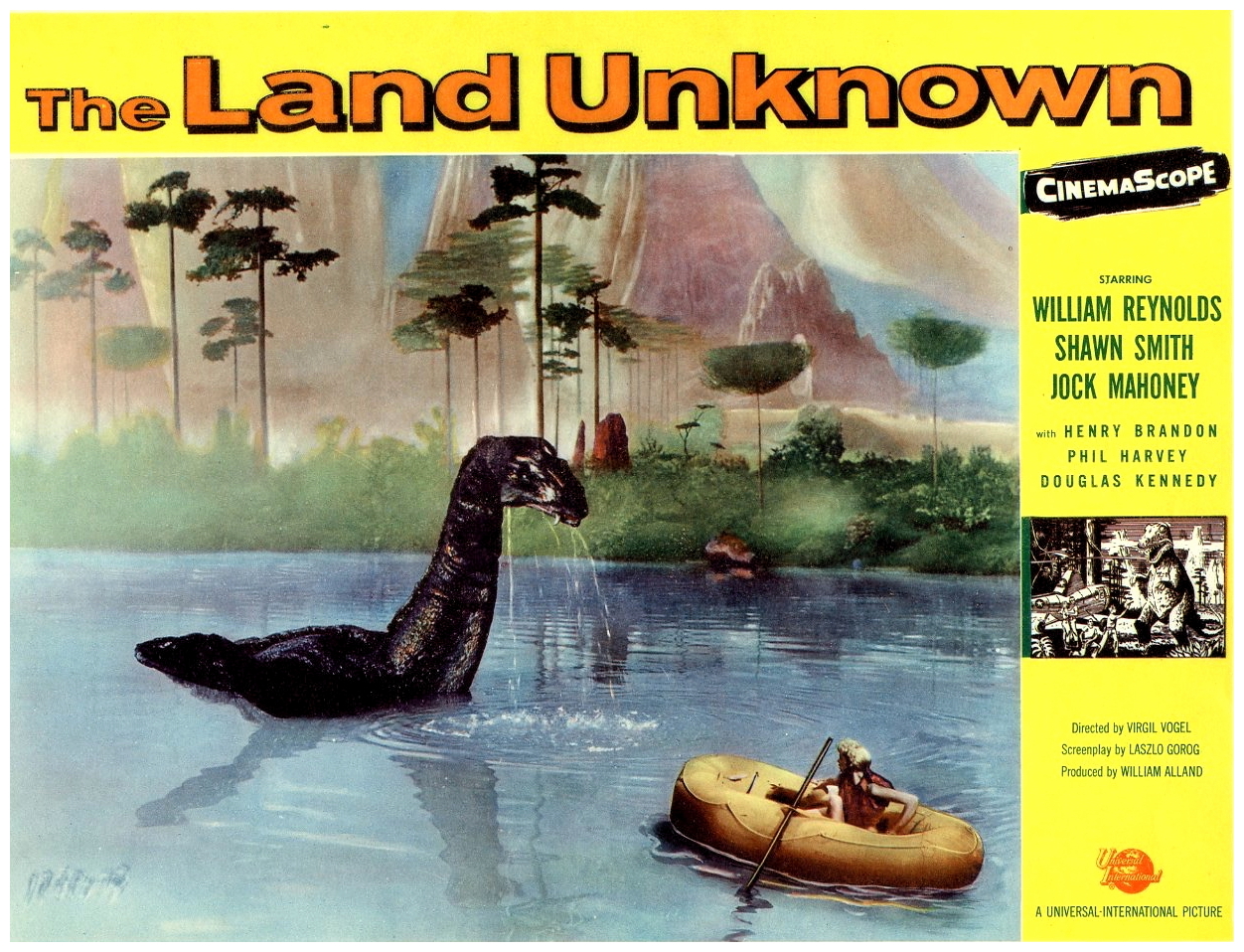

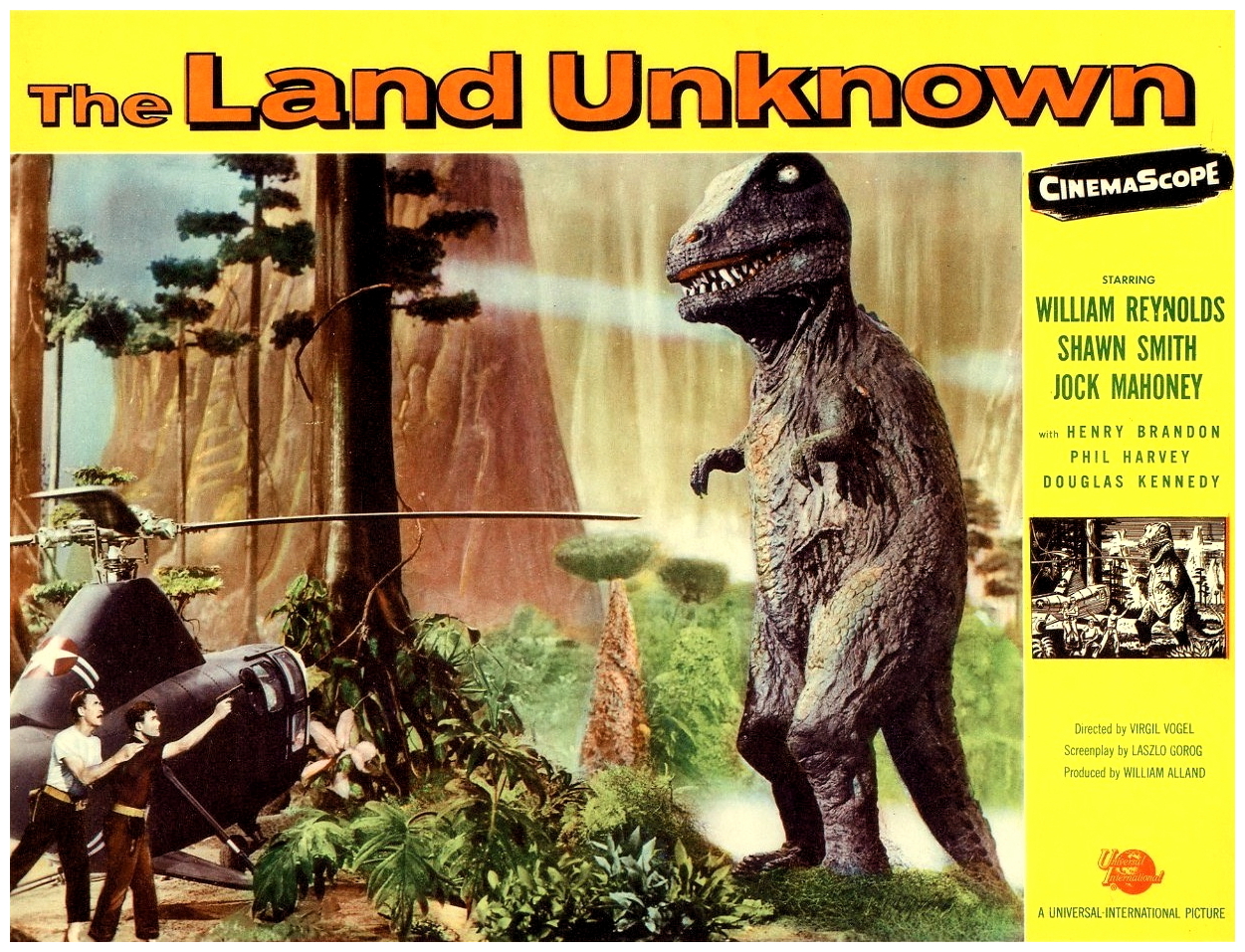

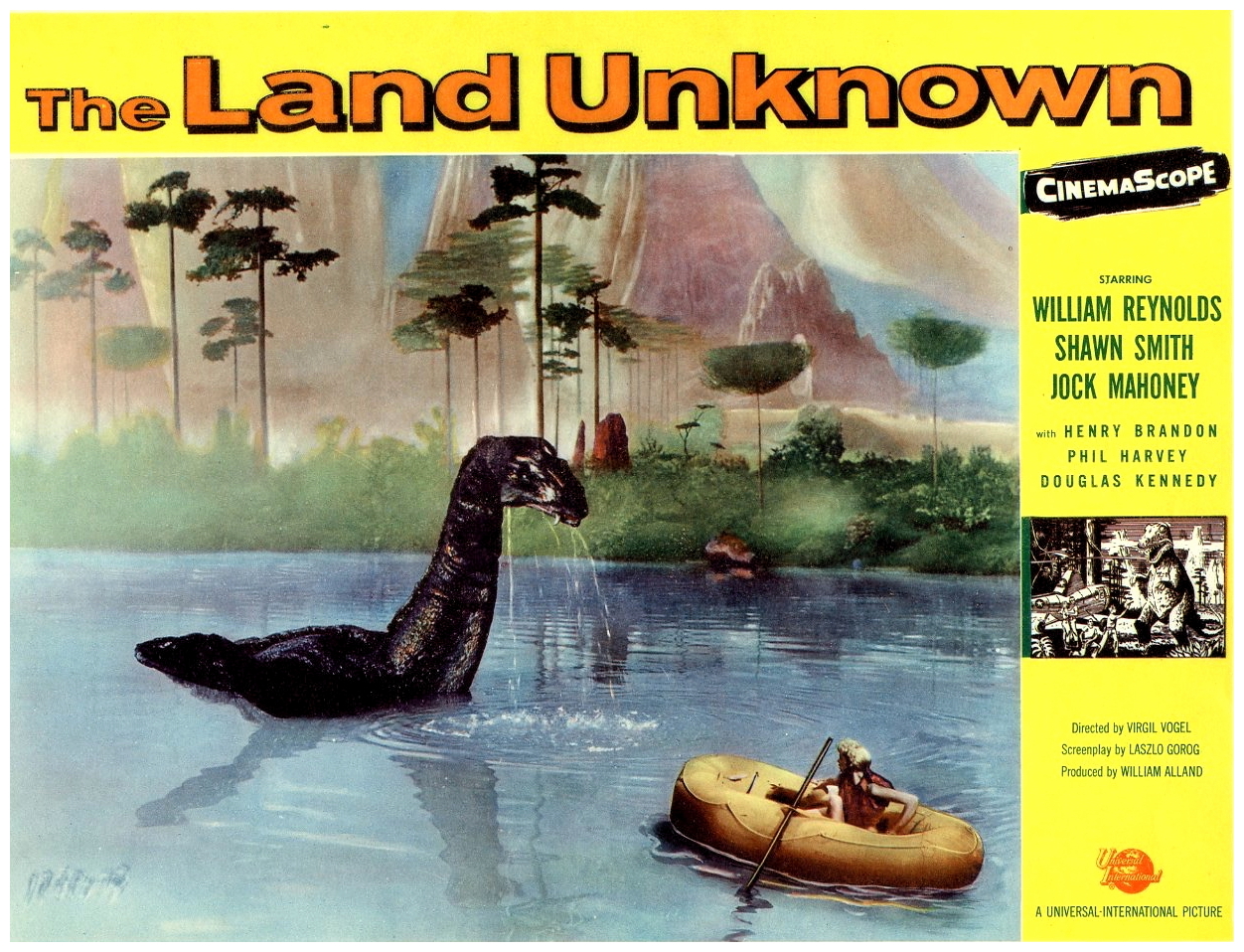

The expedition is soon attacked by a tyrannosaurus which they manage to keep at bay with the whirling helicopter blades, and the monster is driven off by a mysterious piercing sound. Later, the expedition finds the source of this life-saving noise. They come upon Doctor Carl Hunter (Henry Brandon) who, ten years earlier, had survived a plane crash in the valley and had somehow managed to survive in the prehistoric jungle. The sound that scared away the tyrannosaurus came from a special horn built by Hunter to ward off the beasts. Hunter still has some of the parts from his downed plane, parts that could be used to repair the damaged helicopter. With his ragged clothes and matted beard, Hunter may appear deranged, but he’s not as crazy as he looks – in return for the needed parts, he insists he be given Miss Hathaway. The heroic Roberts naturally refuses then, eventually, wins Hunter’s trust and persuades him to help out. After a running battle with a ferocious aquatic dinosaur (an elasmosaurus) the expedition is able to repair the helicopter and fly up out of the chasm to leave The Land Unknown behind.

The project already had an interesting history by the time it came into Vogel’s hands. The original story treatment was written by Willis O’Brien, the immortal stop-motion animator who brought King Kong (1933) and Mighty Joe Young (1949) to life. O’Brien, however, never received screen credit for his treatment, the credit went instead to Charles Palmer. The original director assigned to the film was Jack Arnold, the master of fifties science fiction whose credits include It Came From Outer Space (1953), Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954) and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). Had O’Brien overseen The Land Unknown, he undoubtedly would have created the dinosaurs through the process of animation, but director Arnold opted instead for full-scale animatronics for which he conceived the original designs. The mechanical approach to the dinosaurs suited Vogel fine because he had never cared for animated miniatures, and leading the effects team was Clifford Stine.

“When I took over the directorship we had all the plans, and I jumped into it with Cliff Stine. We changed some things to fit my ideas. He was my right-hand man. When we were shooting on the stage, he would come down and was always behind me. Any time I wanted anything, he was there to help.” The animatronic tyrannosaurus was four metres tall and was designed to house a man inside. The actual construction was done by makeup man Jack Kevan. The model trailed a series of hydraulic wires, each one corresponding to a separate moveable part (mouth, eyes, etc.) and were connected to an off-screen control panel where a technician operated all the monster’s working features. The man inside the model just kept the legs moving, and the model was filmed on miniature sets to give the beast a towering appearance (Universal recycled the full-size model as Spot, the fire-breathing dragon under The Munsters‘ staircase). The three-metre tall aquatic elasmosaurus was engineered by Fred Knoth. The creature was moved along metal tracks concealed underwater and the hydraulics, designed and operated by Orien Ernest, worked the neck, mouth and flippers.

The aerial models (the pterodactyl and the helicopter) were the province of Charlie Baker. The miniatures were combined on-screen with the actors usually by one of two methods. In some cases, the scaled-down dinosaurs were rear-projected behind the actors performing on a full-scale set. In other cases, a split-screen was used. The scene would be divided in half, and the actors would be filmed on one side while the monsters would be shot separately on the other side. To help set up these encounters, every scene in the picture was storyboarded well in advance of the actual shooting. In addition to elaborate effects, imaginative production design was essential. The freakish jungle that the expedition finds had a very strange otherworldly look to it, thanks to the first-rate pre-production planning of designers Alexander Golitzen and Richard Reidel. Reidel learned his craft in the German expressionistic school of filmmaking during the silent era. This artistic bent was most apparent in the exaggerated perspective of the stark sets Reidel designed for The Son Of Frankenstein (1939).

They were described as ‘psychological sets’ because they were intended primarily to influence the mind of the viewer rather than to appear realistic. In The Land Unknown, Reidel made a point of stylising the jungle as much as possible to create a unique appearance. Golitzen, his co-designer, worked along similar lines. The plants in the jungle were typical of vegetation found in that sort of tropical climate, except they were planted upside-down – their roots rather than their leaves were exposed to add to the weird effect. Golitzen, who won Oscars for his work on Phantom Of The Opera (1943) and Spartacus (1960), regarded The Land Unknown as one of his favourite assignments. Curiously, the most difficult problem Vogel faced when shooting this story about desperate encounters ferocious prehistoric monsters, did not have to do with intricate mechanical dinosaur models. “The biggest headaches to overcome on the show were the problems in shooting. We had a large, large stage. It had a big pool in it, much bigger than an olympic pool. We had to fog that in, make a shot and, after we made a shot, the stage had to be cleared of fog to re-set up the next one. We got about four shots a day. Normally you should get about thirty.”

The mammoth pool that stood in for the warm Antarctic lake also figured into star Jock Mahoney‘s worst moment in the shooting. As a former stuntman, Mahoney never used a body-double, and ended up receiving a nasty injury. In one scene in which he jumped from the helicopter to the water below, he suddenly landed on something metallic and injured himself on impact. He was never sure exactly what it was, either the underwater tracks used to manipulate the elasmosaurus or some containers holding the underwater plants. Either way, the pool proved to be an unlucky place for both director and actor. Unfortunately, after all this hard work, the tyrannosaurus looks rather pitiful, but keep in mind that the movie is a product of the fifties and, in fact, the tyrannosaurus is the only truly weak element in an overall decent and spirited effort. The Land Unknown also boasts an adequate screenplay, solid performances and direction, and the pterodactyl and elasmosaurus are far more successful. The imaginative photography manages to make real-life iguanas and lizards look menacing.

Okay, so The Land Unknown does get rather tacky at times and often becomes tedious, but it’s undeniably charming and the opening quarter is even educational, with actual footage of the historically fundamental Admiral Byrd expeditions. It was shot in ninety days, which must have seemed like a luxury to Vogel after the scant seventeen days used to shoot The Mole People. Even so, a three-month shooting period is hardly a generous amount of time to film such a complicated effects movie. But, as in The Mole People, Vogel made the most of the time and resources allotted to him to make The Land Unknown, one of the more memorable fantasy films of the fifties. Hold that thought, and I’ll politely ask you to please join me again next week to discover if Hollywood has yielded up another work of substance, or a nonsensical bit of fluff for…Horror News! Toodles!

The Land Unknown (1957)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews