SYNOPSIS:

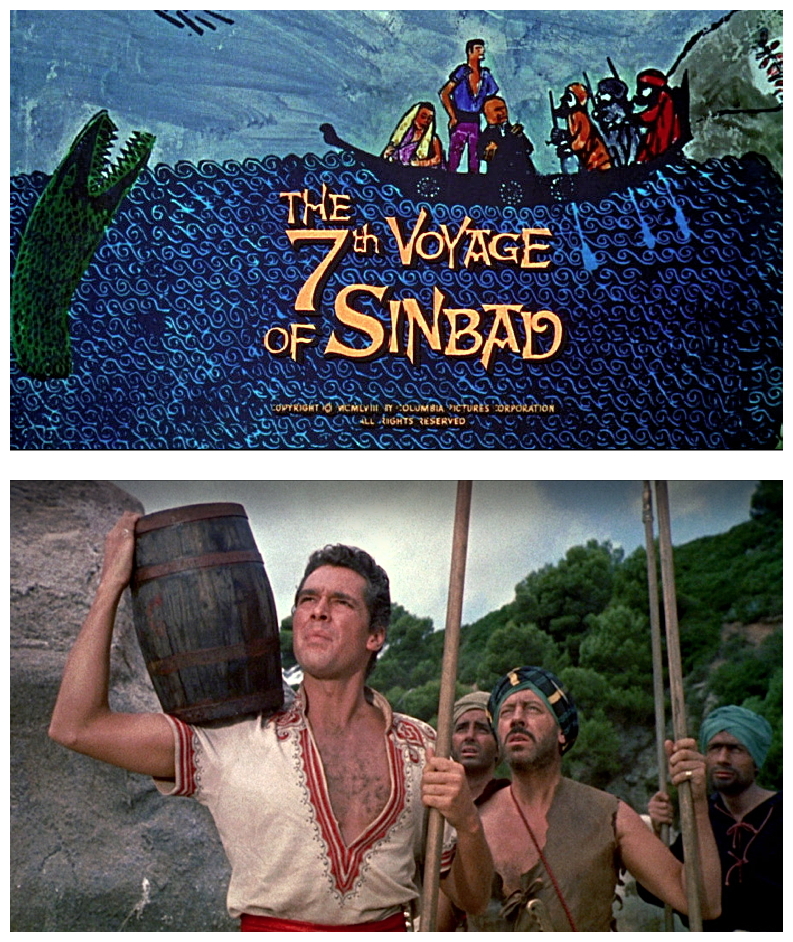

“While sailing with Princess Parisa to Baghdad to their wedding, Sinbad finds the Colossa Island and anchors his vessel to get supplies for the starving crew. Sinbad and his men help the magician Sokurah to escape from a Cyclops that attacks them, and Sokurah uses a magic lamp with a boy jinni to help them; however, their boat sinks and he loses the lamp. Sokurah offers a small fortune to Sinbad to return to Colossa, but he does not accept and heads to Baghdad. The citizens and the Caliph of Baghdad are celebrating the peace with Chandra, and they offer a feast to the Sultan of Chandra. Sakurah requests a ship and crew to return to Colossa but the Caliph refuses to jeopardise his countrymen. However, the treacherous magician shrinks the princess and when the desperate Sinbad seeks him out, he tells that he needs to return to Colossa to get the ingredient necessary for the magic potion. But Sinbad has only his friend Harufa to travel with him, and he decides to enlist a doubtful crew in the prison of Baghdad, in the beginning of his dangerous voyage to Colossa to save the princess and avoid the eminent war between Chandra and Baghdad.”

REVIEW:

The most famous animated creature in film history was King Kong (1933), built and manipulated by Willis O’Brien. A decade later O’Brien was working on another giant ape movie called Mighty Joe Young (1946) and hired a young assistant, Ray Harryhausen. During the fifties it became clear that Harryhausen had inherited O’Brien’s mantle as the top stop-motion animator in the film business, a position which, in the eyes of many, he continues to hold. Stop-motion animation is done by photographing models one frame at a time to give the illusion that they are in motion when the film is played back (the models are normally constructed around flexible armatures), and then optically combining the results with live action, often using a technique known as the traveling matte. When live action is combined with the animated miniature, tricks can be played with scale, so that a model less than a foot tall can appear to loom up like a colossus.

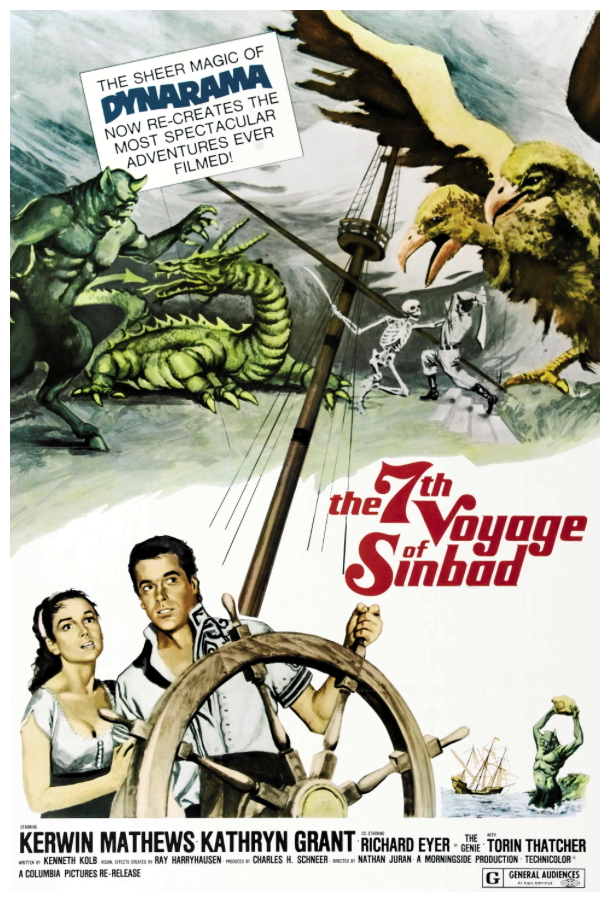

O’Brien, who passed away in 1962, lived long enough to see some of his former pupil’s success, though most of the early films on which Harryhausen worked were comparatively minor: The seminal Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and Twenty Million Miles To Earth (1957). But in the late fifties Harryhausen, along with the producer with whom he nearly always worked, Charles Schneer, had a breakthrough film, The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad (1958). Very much an exotic fairy-tale largely aimed at children, but with a love interest as well, it turned out to appeal to children of all ages. The time was obviously ripe for this sort of romantic fabled based loosely on traditional mythologies. The Italians had just had a big success with a truly dreadful film starring muscleman Steve Reeves called Hercules (1957), and many Hercules films were to follow, each with at least one monster for the giant-thewed hero to subdue. Hercules was very successful in the USA, too.

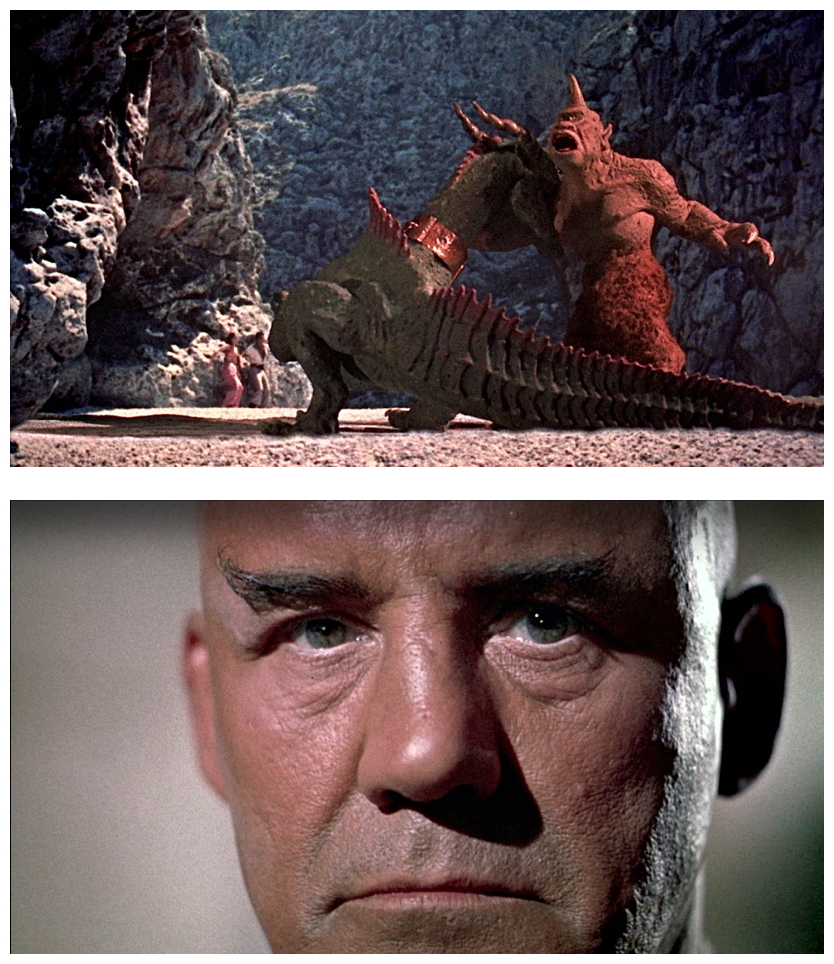

The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad is amusing but, from the beginning, the trouble with Harryhausen’s fantasy films, no matter who directed them (this time it was Nathan Juran), has always been the weak, highly episodic scripts. These seem to be dashed off rather mechanically to link together already-planned sequences featuring people versus monsters. In this case the animated creatures include a cyclops (a one-eyed giant with satyr-like legs), a dragon, a roc (a monstrous two-headed bird), a four-armed snake-woman and, finally, a sword-fighting skeleton modelled for Harryhausen by yours truly. The animated sequences are great fun, and often very well executed, but somehow his films seldom achieve the truly magical. The screenplays are blunderingly literal-minded, and the actors (especially Kerwin Matthews as Sinbad) come from a long way down in the hierarchy and were presumably hired cheap. Films of this kind are adroit, but rather crude, too.

It may be paradoxical to suggest it, but although they have devoted much of their lives to the craft, Harryhausen and Schneer seem to have no more than a novice’s appreciation of what elements constitute true fantasy. For one thing, The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad never suggests anything by implication, by creating subtleties in atmosphere. Animated fantasies of this sort is typically show the fantastic straight-on, in good light and, in this case, colour. In fact it was the first feature using stop-motion animation effects to be completely shot in colour. There are great difficulties in combining animation with live action, and one feels for poor Kerwin Matthews, who had to learn a sword-fight stroke-perfect, and use it against empty air (my miniature double was added afterwards), while looking as if something was there. By this time, Harryhausen had named his animation process Dynamation, its unusual feature was that in the optical combination of live action and animation, he would sometimes have live action in the background, then the animated model in the mid-ground, and more live action in the foreground.

Even sophisticated audiences used to animated figures against a real background were impressed by this sandwiching effect, which certainly heightened the illusion. On the other hand, the models in The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad have a slightly mechanical feel to them, as they almost always do in this kind of film. This is partly because every individual frame of animation is entirely still, whereas in ordinary films individual frames are very often blurred. When a succession of individually motionless frames is played back, a stroboscopic effect can be produced. This is to do with the way in which the brain perceives images and runs them together to produce the illusion of motion. No matter how smoothly the animation is achieved, the end result can still be jerky because of strobing. Schneer and Harryhausen had taken a risk with The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad. The conventional wisdom of the time held that Arabian Nights fantasies like The Thief Of Bagdad were now old hat.

The last success in the genre had been a decade before with Sinbad The Sailor (1947) starring Douglas Fairbanks Jr, so it was a great relief when the film did extremely well. A factor that certainly helped was the energetic musical score by Bernard Herrmann, one of his best. Initially, Harryhausen wanted Miklós Rózsa or Max Steiner to score the film, but Schneer insisted on Herrmann instead. Herrmann’s score was so well received, and he worked so well with Schneer and Harryhausen, he ended up scoring three more of their films: The Three Worlds Of Gulliver (1960), Mysterious Island (1961) and Jason And The Argonauts (1963). Harryhausen eventually got his wish, however, when Miklós Rózsa scored The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad (1971). Harryhausen worked steadily on a variety of fantasy projects with Schneer over the following few years, including The Three Worlds Of Gulliver and Mysterious Island. His next major mythological project, however, was Jason And The Argonauts, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll bid you a good night and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to raise the hackles on your goose-bumps with more ambient atmosphere so thick you could cut it with a chainsaw, in yet another pants-filling fright-night for…Horror News! Toodles!

The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad (1958)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews