SYNOPSIS:

A young couple out for a walk decide to take a stroll through a large cemetery. As darkness begins to fall they realize they can’t find their way out, and soon their fears begin to overtake them.

REVIEW:

“How did you get here?”

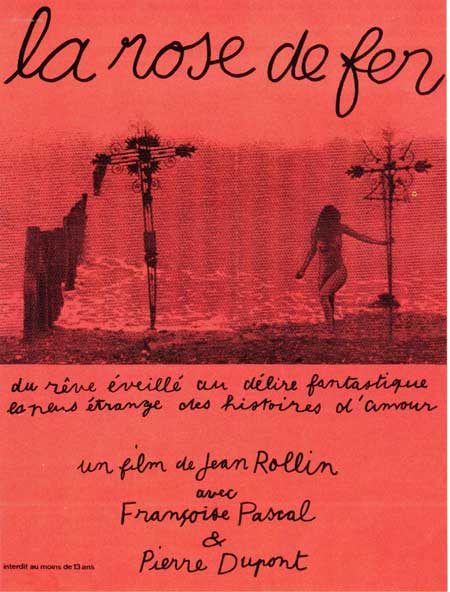

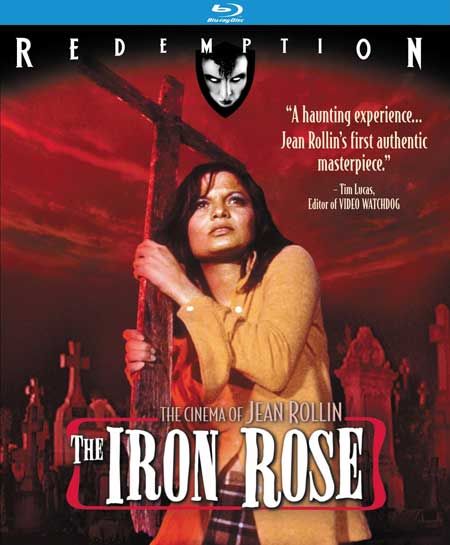

Jean Rollin’s The Iron Rose (also known as The Crystal Rose) is a significant early entry in his filmmaking career as being just as representative as his more lauded works (such as Les raisins de la mort, Fascination, and La morte vivante) and also incredibly discordant amongst critics and fans of his work. Many of Rollin’s films were underappreciated at the initial time of their release (particularly in his native homeland) as a reaction to his distinctive approach to a typically one-note genre. Here, however, it was not violence and nudity which audiences rejected but the lack of it. An oft-heard grievance about the film is the lack of plot but all this really means is that questions are not answered directly.

There is a wedding reception. There are many people are chatting, some seem to know each other some don’t. A young man (Hughes Quester) is seated at a table apparently bored. He notices a young woman (Francoise Pascal) at the other end of the room also apparently bored. He announces softly (so softly it is bizarre that everyone becomes quiet) that he has a poem to recite: “Dying in his sleep, he lived in his dreams. His dream was a tide flowing up the side, the tide flowing down, your eyes in those eyes, your lips on that lip. It is to you that I bade farewell to life, you who mourned me to the point I wanted to mourn myself.” Inexplicably, everyone seems to know he’s reciting it to her.

They arrange to meet the next day at a derelict railway station. They then bike to a large cemetery. It is still daylight but she is hesitant, he is irreverent. They enter. They picnic atop a grave, they make love in a tomb (accompanied by a wonderful soundtrack of bones knocking together – only you, Jean, only you), meanwhile, we observe an old woman leaving by the large entrance gate and a clown who lays flowers at a grave. It becomes dark and the lovers emerge. They begin their trek back to the entrance and the man realizes his watch (time) is gone and the path (space), which the man seemed to know in daylight, disappears and they become lost. Finally, the woman becomes temperamental, even hysteric. In turn, the man becomes erratic. They bicker, they make love, they assault each other. Rollin described the film as “a woman’s dramatic self-destruction,” and one staple he retains here is his macabre eroticism (but no lesbians this time). As a side note, the cemetery itself is none other than the cimetiere de Montmartre, a massive necropolis overpopulated with corpses and overgrown with neglect. One can feel Rollin’s fascination (no pun intended) with the location as he lovingly caresses every tombstone, every distinctive monument, and it really does seem like we never see anything twice.

And so, we arrive at the title in question. A recurring motif in the film is a scene of the woman finding a rose made of iron washed up on a beach but we are never informed as to when this occurs. As with much of Rollin’s work, dream, reality, past, and present often coalesce into a single distinct existence. One must assume this recurrence is symbolic, perhaps responsible, for the woman’s seemingly erratic behavior. It is also interesting to point out that in nearly all of Rollin’s films this beach makes an appearance often in surreal sequences possibly associative with the unexpected (but inevitable) flotsam of the events in one’s life (or thoughts in one’s mind). The beauty of Rollin is that he invites, but never expects, us to intellectualize.

This is Rollin in his most unadulterated form. Now does that mean this is his “best” film (whatever that means)? Perhaps not (though that is arguable) but it is his most representative in that he is never tethered to any outside convention (he reportedly made the film with the expectation that it would not prove lucrative – and he was right) and nothing is ever contrived. Atmosphere is first and foremost but there is a steady undercurrent of mockery as well, as the two lovers beat on each other and lose their minds it’s not unfathomable that such would happen to anyone in the early ‘70s lost in a cemetery at night post-Night of the Living Dead. Always a visionary, Rollin is at his most lyrical: the architecture of the headstones, of the young lovers’ bodies, perfect framing and always consistent composition. The ever-present third character is, of course, the cemetery itself which seems to be a reformative loop showing another face of the same decay, promising release but never relinquishing. There is also a fourth character, a presence neither we nor the characters can see, an influence that is felt like breath to the ear. Powerless to define it, there is only to acquiesce and that is all.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews