“On January 5th 1900, a disheveled looking H.G. Wells – George to his friends – arrives late to his own dinner party. He tells his guests of his travels in his time machine, the work about which his friends knew. They were also unbelieving, and skeptical of any practical use if it did indeed work. George knew that his machine was stationary in geographic position, but he did not account for changes in what happens over time to that location. He also learns that the machine is not impervious and he is not immune to those who do not understand him or the machine’s purpose. George tells his friends that he did not find the Utopian society he so wished had developed. He mentions specifically a civilisation several thousand years into the future which consists of the subterranean Morlocks and the surface dwelling Eloi, who on first glance lead a carefree life. Despite all these issues, love can still bloom over the spread of millennia.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

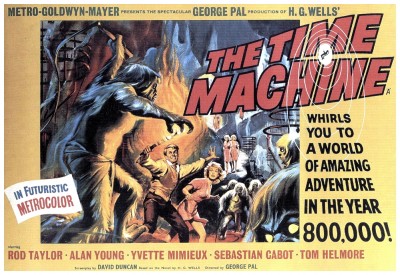

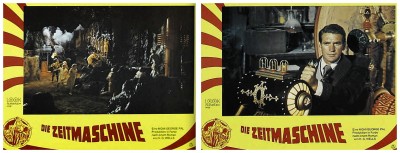

Having graduated from short animated Puppetoons for children during the forties, Hungarian-born producer-writer-director George Pal was the creative mind behind a number of special effects-driven films that set the scene for American science fiction cinema during the fifties and sixties. Obviously feeling quite chuffed with the success of The War Of The Worlds (1953), Pal chose to adapt another H.G. Wells story. The result was The Time Machine (1960). Again the effect was weakened by using a rather conventionally handsome inflexible actor as hero: The War Of The Worlds had Gene Barry, and The Time Machine had Australian Rod Taylor. And once again, the intellectual complexity of the original was pared down to straightforward adventure.

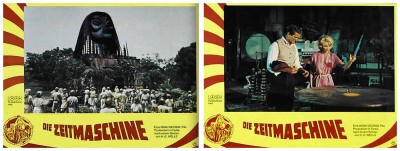

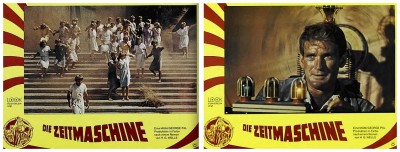

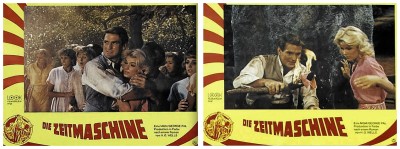

The best sequences of the film show the optimistic time traveler going into the future, pausing occasionally to watch London changing, only to be bitterly disappointed that time and again the world is at war. Fleeing a nuclear war in 1966, he zooms into the far-flung future year of 802,701. There he finds a colony of Eloi – young, blonde, ignorant, apathetic, carefree people living in an Eden-like garden. When a young woman named Weena (Yvette Mimieux) almost drowns, he is appalled that he is the only person who attempts to rescue her, and he is repelled by how far mankind has sunk: Their lack of culture; their work-free existence; and their refusal to defend themselves against the Morlocks who live below ground.

The best sequences of the film show the optimistic time traveler going into the future, pausing occasionally to watch London changing, only to be bitterly disappointed that time and again the world is at war. Fleeing a nuclear war in 1966, he zooms into the far-flung future year of 802,701. There he finds a colony of Eloi – young, blonde, ignorant, apathetic, carefree people living in an Eden-like garden. When a young woman named Weena (Yvette Mimieux) almost drowns, he is appalled that he is the only person who attempts to rescue her, and he is repelled by how far mankind has sunk: Their lack of culture; their work-free existence; and their refusal to defend themselves against the Morlocks who live below ground.

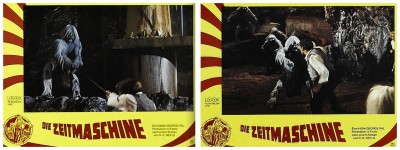

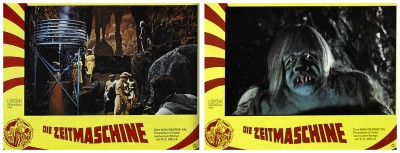

These hideous mutants of nuclear war provide plenty of fruit to feed the Eloi but, being carnivorous, the Morlocks use the passive Eloi much like cattle for all their meat-eating needs. While George recognises a weak trace of their former humanity even in the Morlocks, Pal’s protagonist is incensed by their inhumanity. He is sympathetic to the Elois essential goodness, and their helplessness against their inhuman exploiters, and accepts as an ethical imperative the task of liberating them from their Utopian indolence and advancing them to hard work and technological progress.

These hideous mutants of nuclear war provide plenty of fruit to feed the Eloi but, being carnivorous, the Morlocks use the passive Eloi much like cattle for all their meat-eating needs. While George recognises a weak trace of their former humanity even in the Morlocks, Pal’s protagonist is incensed by their inhumanity. He is sympathetic to the Elois essential goodness, and their helplessness against their inhuman exploiters, and accepts as an ethical imperative the task of liberating them from their Utopian indolence and advancing them to hard work and technological progress.

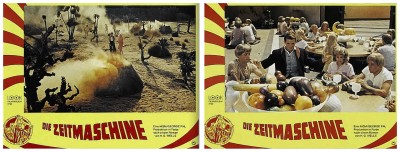

He may dress like a Victorian Englishman, but Pal’s protagonist is an all-American two-fisted hero who brings to the Eloi the profound message that a good punch on the jaw will solve anything. His example finally jolts them out of their fatal lethargy and within moments they are all gleefully committing acts of violence. With their assistance George manages to set fire to the Morlocks underground establishment and everyone lives happily ever after – providing the Morlocks from neighbouring districts don’t move in – it’s unlikely that all the Eloi and Morlocks in the world are restricted to one small area, after all.

He may dress like a Victorian Englishman, but Pal’s protagonist is an all-American two-fisted hero who brings to the Eloi the profound message that a good punch on the jaw will solve anything. His example finally jolts them out of their fatal lethargy and within moments they are all gleefully committing acts of violence. With their assistance George manages to set fire to the Morlocks underground establishment and everyone lives happily ever after – providing the Morlocks from neighbouring districts don’t move in – it’s unlikely that all the Eloi and Morlocks in the world are restricted to one small area, after all.

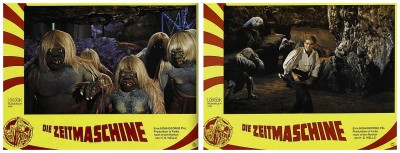

Gene Warren, Wah Chang and Tim Barr won an Oscar for their well-crafted special effects. In fact the design is quite successful throughout, but Wells’ grim allegory of evolution (the grotesque symbiosis of the working classes feeding cannibalistically upon the elite capitalist classes they serve) is lost. Here the Morlocks are nothing more than stereotyped hairy ape-people. George Pal, who also directed, chose to ignore Wells’ intention to set up two distinct classes, as well as the author’s application of Social Darwinism to the survivors of a nuclear war. Instead, the film deals with how the Eloi make the choice not to be cattle raised for slaughter, but to regain their human traits – care for each other, fight for survival, gather food, work hard – which are distinct from the beastly traits of the Morlocks.

Gene Warren, Wah Chang and Tim Barr won an Oscar for their well-crafted special effects. In fact the design is quite successful throughout, but Wells’ grim allegory of evolution (the grotesque symbiosis of the working classes feeding cannibalistically upon the elite capitalist classes they serve) is lost. Here the Morlocks are nothing more than stereotyped hairy ape-people. George Pal, who also directed, chose to ignore Wells’ intention to set up two distinct classes, as well as the author’s application of Social Darwinism to the survivors of a nuclear war. Instead, the film deals with how the Eloi make the choice not to be cattle raised for slaughter, but to regain their human traits – care for each other, fight for survival, gather food, work hard – which are distinct from the beastly traits of the Morlocks.

The film is not without its moments though. For example, the diseased white sphinx statue of the original is still there but, overall, it is an appalling vulgarisation of a great novel, and is one of the instances that caused science fiction fans to wonder if science fiction cinema would ever rise above its preoccupation with adventure and spectacle to produce something to excite the mind. That being said, the film itself does have adventure and spectacle, an excellent opening scene, superb time-travel effects, scary-looking monsters, and a pleasing though too-innocent love affair.

The film is not without its moments though. For example, the diseased white sphinx statue of the original is still there but, overall, it is an appalling vulgarisation of a great novel, and is one of the instances that caused science fiction fans to wonder if science fiction cinema would ever rise above its preoccupation with adventure and spectacle to produce something to excite the mind. That being said, the film itself does have adventure and spectacle, an excellent opening scene, superb time-travel effects, scary-looking monsters, and a pleasing though too-innocent love affair.

Speaking of which, The Time Machine was the lovely Yvette Mimieux‘s first claim to fame, and immediately followed through with the first teenage-girl road-movie Where The Boys Are (1960). Her career quickly deteriorated to roles in rarely screened B-grade films like Three In The Attic (1968), The Neptune Factor, Journey Into Fear (1975) and Devil Dog The Hound Of Hell (1978). Just when it looked like it couldn’t get any worse, Yvette co-starred in what was to become one of Disney’s most infamous films of all-time: The Black Hole (1979). But I digress.

Speaking of which, The Time Machine was the lovely Yvette Mimieux‘s first claim to fame, and immediately followed through with the first teenage-girl road-movie Where The Boys Are (1960). Her career quickly deteriorated to roles in rarely screened B-grade films like Three In The Attic (1968), The Neptune Factor, Journey Into Fear (1975) and Devil Dog The Hound Of Hell (1978). Just when it looked like it couldn’t get any worse, Yvette co-starred in what was to become one of Disney’s most infamous films of all-time: The Black Hole (1979). But I digress.

Given the popularity of the original novel, Pal’s film stays relatively close to the basic plot but, despite its melancholic evocation of late-Victorian London, the warm glow of its patented Metrocolor palette, the steam-punkish quaintness of its models and miniatures, and its time-lapse and stop-motion effects, Pal’s film is not an exercise in nostalgia. Rewritten for American audiences at the height of the Cold War, it is anchored firmly in the global politics of the time. Where Wells’ novel features a scene of dark cosmic grandeur in which two feeble cretaceous descendants of humankind struggle mutely toward each other, in a distant future beneath a dying sun, Pal takes us through a twentieth century of perpetually escalating warfare, culminating in the annihilation of London by an atomic satellite that triggers natural disasters on an unprecedented scale. As in The War Of The Worlds, some of the most spectacular scenes in The Time Machine revel in howling air-raid sirens, urban crowds fleeing to public shelters, destruction on a massive scale.

Given the popularity of the original novel, Pal’s film stays relatively close to the basic plot but, despite its melancholic evocation of late-Victorian London, the warm glow of its patented Metrocolor palette, the steam-punkish quaintness of its models and miniatures, and its time-lapse and stop-motion effects, Pal’s film is not an exercise in nostalgia. Rewritten for American audiences at the height of the Cold War, it is anchored firmly in the global politics of the time. Where Wells’ novel features a scene of dark cosmic grandeur in which two feeble cretaceous descendants of humankind struggle mutely toward each other, in a distant future beneath a dying sun, Pal takes us through a twentieth century of perpetually escalating warfare, culminating in the annihilation of London by an atomic satellite that triggers natural disasters on an unprecedented scale. As in The War Of The Worlds, some of the most spectacular scenes in The Time Machine revel in howling air-raid sirens, urban crowds fleeing to public shelters, destruction on a massive scale.

After the many pleasures provided by The Time Machine, Pal’s next film – Atlantis The Lost Continent (1961) – came as a severe letdown. The scenes of destruction at the end of the film also suffered from the shoestring budget, despite being padded out with stock footage of Rome burning from Quo Vadis? (1951), but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations ever to be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

After the many pleasures provided by The Time Machine, Pal’s next film – Atlantis The Lost Continent (1961) – came as a severe letdown. The scenes of destruction at the end of the film also suffered from the shoestring budget, despite being padded out with stock footage of Rome burning from Quo Vadis? (1951), but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations ever to be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews