“Health food store owner and wannabe jazz clarinetist Miles Monroe is involuntarily cryogenically frozen in 1973 after a mishap while in minor surgery. His still frozen body is found in 2173, and unfrozen by scientists Melik and Orva. In unfreezing Miles, the doctors have committed an illegal act in what is now a totalitarian police state, where records of the past have been destroyed and the resulting history unknown. The society is filled primarily of conformists who look to the state’s ‘leader’ for guidance. The doctors, working with an underground group of revolutionaries based in what is called the Western District, ask Miles to help the revolutionaries infiltrate the state’s secret and highly important Aries project. Their rationale is that Miles does not exist in the eyes of the state and thus if captured cannot provide any information to them. In Miles’ reluctant journey to the Western District, he co-opts the initially unwilling assistance of one of the conformists, poet Luna Schlosser, in trying both to reach the Western District and avoid capture by the police. As a non-political person who believes that all leaders are self-interested, Miles, even when learning the nature of the Aries project, has the primary goals of staying alive and getting the girl, as he is starting to fall in love with Luna, who may have her own thoughts about love and life in this society.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

The old Monster-From-Outer-Space type of film, so plentiful back in the fifties, had almost completely died out by the time early seventies came around. The cliches of science fiction began to provide the subject for a handful of comedy films during the early seventies, the best of which came from comedian-writer-director-actor Woody Allen. He first touched upon the subject of science fiction with Everything You Ever Wanted To Know About Sex But Were Afraid To Ask (1972), which was based very loosely on David Reuben‘s book of the same name. Consisting of short episodes satirising various aspects of sex, the film includes two segments that can be described as science fiction parodies. One involves a mad scientist (John Carradine sending up a role he’s played many times before) who creates a giant mobile breast that breaks out of his laboratory and ravages the countryside drowning its victims in milk, until it’s trapped by Woody wielding a crucifix, who lures it into a giant bra.

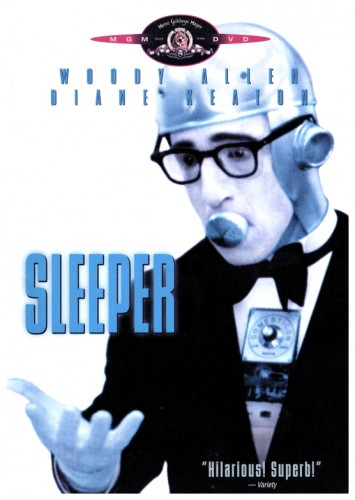

The other segment plays around with the old science fiction theme of the human body as some sort of vast machine populated by tiny people. Woody’s version concerns what goes on in this NASA-like organisation during a seduction attempt in the back seat of a car. Up in the Brain Room, looking like a sterile-clean set from The Andromeda Strain (1971), white-suited technocrats (Tony Randall and Burt Reynolds) try to keep things running on schedule, despite being hindered by the overworked proles in the lower regions. These episodes turned out to be a practice run for Woody’s full-length science fiction satire called Sleeper (1973), which he wrote, directed and stars in.

The other segment plays around with the old science fiction theme of the human body as some sort of vast machine populated by tiny people. Woody’s version concerns what goes on in this NASA-like organisation during a seduction attempt in the back seat of a car. Up in the Brain Room, looking like a sterile-clean set from The Andromeda Strain (1971), white-suited technocrats (Tony Randall and Burt Reynolds) try to keep things running on schedule, despite being hindered by the overworked proles in the lower regions. These episodes turned out to be a practice run for Woody’s full-length science fiction satire called Sleeper (1973), which he wrote, directed and stars in.

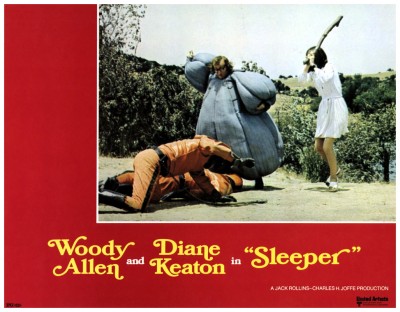

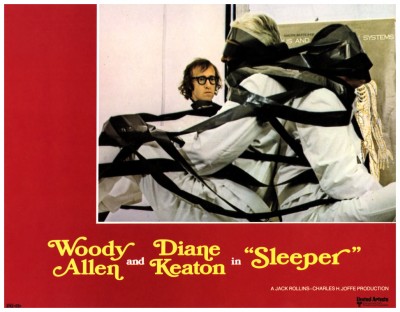

Ordinary ‘little guy’ Miles Monroe (Woody Allen) is a jazz musician from the twentieth century who submits to a minor ulcer operation and wakes up from a two-hundred-year frozen sleep to find himself in this clinical future. Although he’s never been a very political person, he is recruited by the underground to perform a mission that will bring down the totalitarian regime. But Miles finds it difficult to elude the fascist police, and passes himself off as a robot-servant at a party being held by bourgeois hedonist Luna (Diane Keaton). The film becomes a sort-of futuristic version of The Thirty-Nine Steps (1935) when Miles forces Luna to go along with him. At first she screams her head off, but then she too joins the underground. Of course they fall in love.

Ordinary ‘little guy’ Miles Monroe (Woody Allen) is a jazz musician from the twentieth century who submits to a minor ulcer operation and wakes up from a two-hundred-year frozen sleep to find himself in this clinical future. Although he’s never been a very political person, he is recruited by the underground to perform a mission that will bring down the totalitarian regime. But Miles finds it difficult to elude the fascist police, and passes himself off as a robot-servant at a party being held by bourgeois hedonist Luna (Diane Keaton). The film becomes a sort-of futuristic version of The Thirty-Nine Steps (1935) when Miles forces Luna to go along with him. At first she screams her head off, but then she too joins the underground. Of course they fall in love.

Inspired by The Sleeper Awakes by H.G. Wells, Woody uses the device of having a person from the present day finding himself in the future as a means of commenting on contemporary society rather than a genuine attempt of speculating about the future. It takes as its theme a future where human feelings have become – by our standards – minimalised. For instance, orgasm is achieved by entering a special Orgasmatron booth. It only takes a few seconds, and old-fashioned sex is unknown. There’s a lot of slapstick of varying quality and the film alternates between genuine science fiction jokes and contemporary satire. Some of the nicest jokes are about the continuities rather than the differences: McDonalds fast-food is still going strong and a Volkswagen, unused for two centuries, starts first time.

Inspired by The Sleeper Awakes by H.G. Wells, Woody uses the device of having a person from the present day finding himself in the future as a means of commenting on contemporary society rather than a genuine attempt of speculating about the future. It takes as its theme a future where human feelings have become – by our standards – minimalised. For instance, orgasm is achieved by entering a special Orgasmatron booth. It only takes a few seconds, and old-fashioned sex is unknown. There’s a lot of slapstick of varying quality and the film alternates between genuine science fiction jokes and contemporary satire. Some of the nicest jokes are about the continuities rather than the differences: McDonalds fast-food is still going strong and a Volkswagen, unused for two centuries, starts first time.

Other highlights include Miles’ first steps after his long sleep, visiting a robot Jewish tailor, and the philosophical discussions between Miles and Luna about such things as sex and death: “Two things that come only once in a lifetime but at least after death you’re not nauseous.” Diane Keaton in particular is extremely endearing – this is the film where she really came into her own as a comedienne – but too often she sounds like she’s imitating Woody, as opposed to her lines in Annie Hall (1977) which seem to come from Keaton and her character. With neither Woody or Keaton playing it straight, the film sustains the hysterical pitch of a classic screwball comedy. Keaton matches Woody riff-for-riff in a performance that is more layered than his.

Other highlights include Miles’ first steps after his long sleep, visiting a robot Jewish tailor, and the philosophical discussions between Miles and Luna about such things as sex and death: “Two things that come only once in a lifetime but at least after death you’re not nauseous.” Diane Keaton in particular is extremely endearing – this is the film where she really came into her own as a comedienne – but too often she sounds like she’s imitating Woody, as opposed to her lines in Annie Hall (1977) which seem to come from Keaton and her character. With neither Woody or Keaton playing it straight, the film sustains the hysterical pitch of a classic screwball comedy. Keaton matches Woody riff-for-riff in a performance that is more layered than his.

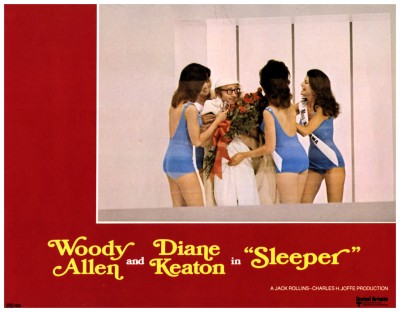

Just as Woody mimics Bob Hope, Keaton proceeds to mimic Woody mimicking Bob Hope. The scene where they are disguised as surgeons pretending to clone the leader from his last remaining body part – his nose – is a fantastic duel performance in which, through their clumsy stalling and stammering, both actors try to out-Woody each other: “We’re going to clone him right into his shoes,” says Woody as he puts the nose at one end of a table and the shoes at the other. But apart from jokes on such early seventies American obsessions as Richard Nixon, health food, beauty contests and revolutionary politics, he also includes a number of pure science fiction gags involving robots, futuristic gadgets, ray guns, mechanised pets and a variety of artificial food that has to be beaten into submission before it can be served.

Just as Woody mimics Bob Hope, Keaton proceeds to mimic Woody mimicking Bob Hope. The scene where they are disguised as surgeons pretending to clone the leader from his last remaining body part – his nose – is a fantastic duel performance in which, through their clumsy stalling and stammering, both actors try to out-Woody each other: “We’re going to clone him right into his shoes,” says Woody as he puts the nose at one end of a table and the shoes at the other. But apart from jokes on such early seventies American obsessions as Richard Nixon, health food, beauty contests and revolutionary politics, he also includes a number of pure science fiction gags involving robots, futuristic gadgets, ray guns, mechanised pets and a variety of artificial food that has to be beaten into submission before it can be served.

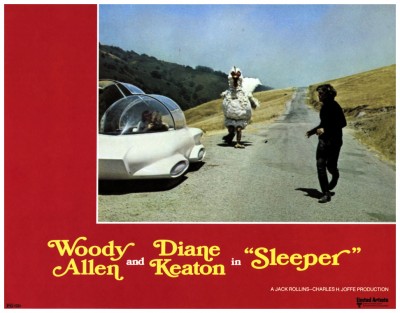

The production design is sixties ‘pop’ combined with seventies ‘chic’ brought to absurd utilitarian levels: A silver orb that looks like a piece of minimalist sculpture is passed around at the party to provide a communal sci-fi-high; The Orgasmatron is a sleek closet-like cylinder that provides its occupants with automated orgasms replete with mechanical moans; The costumes are fun and frivolous, designed by a young Joel Schumacher, more than two decades before he killed off the nineties Batman franchise with Batman Forever (1995) and Batman And Robin (1997).

The production design is sixties ‘pop’ combined with seventies ‘chic’ brought to absurd utilitarian levels: A silver orb that looks like a piece of minimalist sculpture is passed around at the party to provide a communal sci-fi-high; The Orgasmatron is a sleek closet-like cylinder that provides its occupants with automated orgasms replete with mechanical moans; The costumes are fun and frivolous, designed by a young Joel Schumacher, more than two decades before he killed off the nineties Batman franchise with Batman Forever (1995) and Batman And Robin (1997).

Sleeper may not be as polished as Woody’s more recent films, and there’s rather too much emphasis on slapstick but, as an example of that rare species – funny science fiction – it rates very highly. But why is it assumed in ninety percent of all science fiction films made, that future governments will be totalitarian? Perhaps belief in the capitalist system runs shallower than everyone thinks. And it’s on that rather political note I’ll make my fond farewells and politely ask you to please join me again next week to discover if Hollywood has yielded up a work of substance or a nonsensical bit of fluff for…Horror News! Toodles!

Sleeper may not be as polished as Woody’s more recent films, and there’s rather too much emphasis on slapstick but, as an example of that rare species – funny science fiction – it rates very highly. But why is it assumed in ninety percent of all science fiction films made, that future governments will be totalitarian? Perhaps belief in the capitalist system runs shallower than everyone thinks. And it’s on that rather political note I’ll make my fond farewells and politely ask you to please join me again next week to discover if Hollywood has yielded up a work of substance or a nonsensical bit of fluff for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews