SYNOPSIS:

In the 17th Century, encouraged by a naive and sadistic prince, a play is performed about a miraculous child exploited by both his sister and the church. Soon enough, the play becomes all too real, and rape, death and dismemberment follows as the events take on the appearance of an actual religious ritual.

REVIEW:

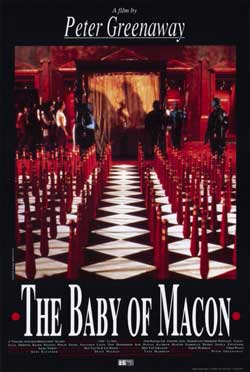

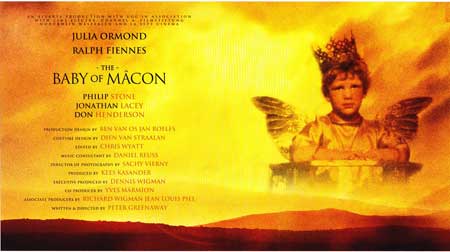

Directed by Peter Greenaway

Starring: Julia Ormand, Ralph Fiennes,

This cold, alienating and repetitive film starts with the ugliest woman in Macon giving birth to a beautiful baby. Those who witness the birth cannot believe that such beauty could be spawned by such a wretch, and begin to question god’s ways. The woman’s virginal daughter (Julia Ormand) has a scheme in mind in which she convinces the town that the child is her own, a “miracle baby”, and pretty soon the child is hailed as a messiah and harbinger of miracles. However, the Bishop’s scientifically inclined son (Ralph Fiennes) has doubts about the whole thing, and so the ‘mother’ invites anyone and everyone to take a peek ‘downstairs’ to prove that she really is a virgin. The following scene sees a queue of people eager to have a look for themselves, and this offers up some comical observations from the menfolk: “Errr… I don’t know what I’m looking for”, admits one. “Her anatomy is most charming”, exclaims another.

The Bishop’s son is still not convinced, so she lures him to a barn in order to prove her virginity once and for all by offering him the chance to take it. She undresses in front of him, and when he can no longer control his lust, he mounts her. But before he can sink it in and pop her cherry, the child shows up unleashing horrific and apparently supernatural powers which causes the man’s body to erupt into a bloody mess. The child reassures his ‘mother’ by reminding her that her virginity is the only thing that is keeping them safe from the wrath of the town. At this point, the back wall of the barn collapses, and behind it is the theatre audience shocked by the sight of Fiennes’ dead body. The Bishop enters and accuses her of killing his son, but when it becomes clear that the murder was an act of divine intervention, all is forgiven.

The woman’s tyranny and sense of self-importance continues to grow in proportion to the adulation which is bestowed upon the miracle child. But when the boy winds up dead – possibly suffocated by the ‘mother’ – the Bishop, still holding a grudge over the death of his own son, sees to it that she is punished in the most horrific way. She teases the Bishop, rightly pointing out that it’s illegal for the church to hang virgins, so he simply orders her to be raped non-stop, 208 times in a row, by the most disease-ridden villagers and the dregs of the local prison. The Bishop forgives the rapists in advance (“You are forgiven, my sons, for making rightful vengeance”), so that all is ‘above board’ in the eyes of god. And while she screams in agony at her harrowing ordeal, the rest of her family are hunted down and hung from the rafters. The child’s body is scalped and cut into pieces so that the mourners can take the body parts home as religious mementos (“Child, bless me with your little feet that walked the earth”), and his severed head is displayed for all to see. The play comes to an end when the ‘mother’ doesn’t survive her ordeal.

The Baby of Macon takes place entirely on stage, and was designed as a puzzling and audacious film which caused outrage when it was screened at the Cannes Film Festival. Having earned himself much arthouse acclaim for his previous hits like Prospero’s Books and The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her lover, director Peter Greenaway took a bit of a detour this time around by heading more towards the blurry line between artifice and actuality, by way of Artaud’s theories on The Theatre of Cruelty. Are these actors being killed ‘for real’ or is it all part of the play? This is the question Greenaway’s fans have been arguing about for the best part of twenty years, as the film simply refuses to clarify the most nagging of questions. All we can say for sure about The Baby of Macon is that the notorious and prolonged rape scene is very nasty, and the dismemberment of the child has kept the film rejected by many American cinema chains over the years.

Greenaway’s favourite DP, Sacha Vierny, returns to point his exquisite lens at another visually stunning concoction. The set designs are amazing; a cathedral decorated and illuminated with thousands of candles that play against the darkness of the auditorium and the script. It was a massive production, with hundreds of extras, live choirs, and string quartets, all making the production seem much grander in scale than its low-budget would suggest. In fact, the visuals and detailed choreography makes Caligula look almost modest in comparison. And the overall grand elegance of the sets and costumes are constantly at odds with the human players, whose hypocrisy and cruelties only adds to the uneasy mix. It’s just a shame that composer Michael Nyman is absent; having made such a strong impact in classics like Drowning By Numbers and The Cook, The Thief…, he fell out with the director, and Greenaway was left to fill the musical holes with traditional classical numbers. It goes without saying that the end result sorely misses Nyman’s magic, and both he and Greenaway still haven’t collaborated on a film project since.

The Baby of Mâcon (1993)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews