SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Svengali is a singing teacher, pianist and general music impresario living in Paris. He has special talents as he is able to mesmerize others through his music and through his strong hypnotic powers. He uses these talents specifically to seduce his female students for his own evil monetary gains. He discards them just as easily when they are no longer of use to him. After he hears her sing (despite she not being a great singer) and sees her, Svengali becomes infatuated with a young model named Trilby O’Farrell who he meets in the studio of some artist colleagues. One of those artists, a young Brit named Billee, and Trilby fall in love with plans of getting married to each other. But after Billee and Trilby have a falling out of sorts, Trilby runs away apparently to commit suicide. Concurrently, Svengali disappears. Svengali resurfaces five years later, married to his singing protégée, the two who perform in concerts together. Billee learns that Madame Svengali is Trilby. Billee vows to follow the pair to save Trilby from whatever special power Svengali holds over her. Knowing that Billee is after them, Svengali has his own plans for his and Trilby’s eternity.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

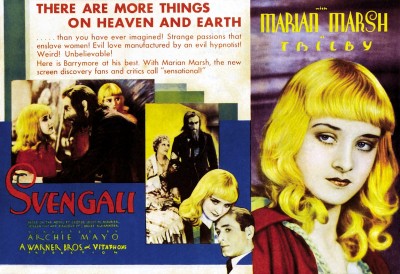

This week I intend to prove wrong all of you who say high quality films are not to be found in the Public Domain, by discussing Svengali (1931). This dusty gem is the best of several versions of George Du Maurier‘s novel Trilby. The character was so well known that the word Svengali, meaning an Evil Mentor, entered the language, but has sadly gone out of use in recent decades.

Svengali is the story of another Mad Artist, a singing teacher this time, and much of it set in Gay Paris, that mecca which all Mad Artists must visit at least once in their lifetime. You may think the Reign Of Terror was the most perilous time to be living in Paris, but considering the films I’ve discussed recently – The Phantom Of The Opera (1925) and Bluebeard (1944) – I’m starting to believe 1890 to 1914 was far more dangerous. There were so many Mad Artists doing nasty things during that time, I wonder why they never thought of forming a Trade Union?

Svengali is the story of another Mad Artist, a singing teacher this time, and much of it set in Gay Paris, that mecca which all Mad Artists must visit at least once in their lifetime. You may think the Reign Of Terror was the most perilous time to be living in Paris, but considering the films I’ve discussed recently – The Phantom Of The Opera (1925) and Bluebeard (1944) – I’m starting to believe 1890 to 1914 was far more dangerous. There were so many Mad Artists doing nasty things during that time, I wonder why they never thought of forming a Trade Union?

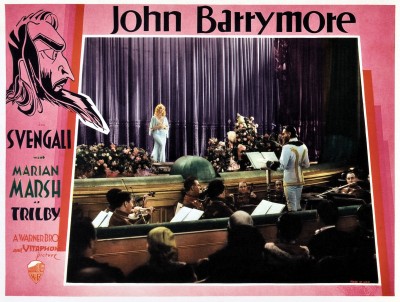

Svengali is played by John Barrymore, one of the most prominent film stars of the day and this is one of his best performances. Yes, it’s true, this John Barrymore is the grandfather of Drew Barrymore, whose acting frightens us for entirely the wrong reasons. But I hasten to point out that John Barrymore passed away in 1942, over thirty years before Drew was born, so those of you who demand a written apology from him will have to wait in vain. I’m confident you’ll enjoy the 1931 classic Svengali as much as I do.

Svengali is played by John Barrymore, one of the most prominent film stars of the day and this is one of his best performances. Yes, it’s true, this John Barrymore is the grandfather of Drew Barrymore, whose acting frightens us for entirely the wrong reasons. But I hasten to point out that John Barrymore passed away in 1942, over thirty years before Drew was born, so those of you who demand a written apology from him will have to wait in vain. I’m confident you’ll enjoy the 1931 classic Svengali as much as I do.

Unlike most films I present on The Schlocky Horror Picture Show, Svengali was made by a major studio, Warner Brothers, and they were able to give it the budget it deserved, as evidenced by the superb photography and the crazy expressionistic sets designed by Anton Grot. A native of Poland, Grot was originally a painter, but by the thirties was one of Warner Brothers most senior set designers, creating more than eighty films for that lucky studio by the time he retired in 1948. Svengali is one of his best. The cavernous rooms and corridors are both amazing and disconnecting. A number of these sets have ceilings, ten years before Orson Welles and Citizen Kane (1941) received credit for that innovation. Trilby standing by that huge door is an unforgettable image, like that large-scale model of Paris. A pinnacle of the model-makers art, it’s a pity we only get to see it once.

Unlike most films I present on The Schlocky Horror Picture Show, Svengali was made by a major studio, Warner Brothers, and they were able to give it the budget it deserved, as evidenced by the superb photography and the crazy expressionistic sets designed by Anton Grot. A native of Poland, Grot was originally a painter, but by the thirties was one of Warner Brothers most senior set designers, creating more than eighty films for that lucky studio by the time he retired in 1948. Svengali is one of his best. The cavernous rooms and corridors are both amazing and disconnecting. A number of these sets have ceilings, ten years before Orson Welles and Citizen Kane (1941) received credit for that innovation. Trilby standing by that huge door is an unforgettable image, like that large-scale model of Paris. A pinnacle of the model-makers art, it’s a pity we only get to see it once.

Directed by Archie Mayo, a prolific but only occasionally distinguished filmmaker, Svengali has moments of humour and many genuine chills. Some of Mayo’s more interesting efforts include The Petrified Forest (1936) and The Black Legion (1936) – both featuring Humphrey Bogart – and A Night In Casablanca (1946), the second-last Marx Brothers film, which probably would’ve been funnier with Humphrey Bogart.

Directed by Archie Mayo, a prolific but only occasionally distinguished filmmaker, Svengali has moments of humour and many genuine chills. Some of Mayo’s more interesting efforts include The Petrified Forest (1936) and The Black Legion (1936) – both featuring Humphrey Bogart – and A Night In Casablanca (1946), the second-last Marx Brothers film, which probably would’ve been funnier with Humphrey Bogart.

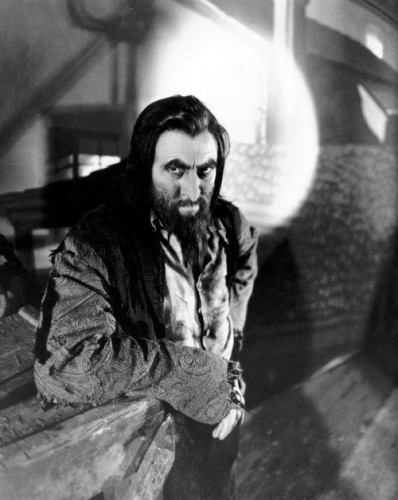

Portraying the sinister Svengali is my old friend John Barrymore, one of the most fascinating characters in film and theatre during the last century. He was son of stage actors Maurice Barrymore and Georgiana Drew Barrymore, and his siblings Ethel and Lionel also had extensive film careers. John made his stage debut in 1900, and quickly became a matinee idol. He entered films in 1913, thanks to the invention of the cinematograph, and although he eventually gave up the stage, it was really his first true love. His Hamlet was widely acclaimed and plans were made to film it, but they came to nothing.

Portraying the sinister Svengali is my old friend John Barrymore, one of the most fascinating characters in film and theatre during the last century. He was son of stage actors Maurice Barrymore and Georgiana Drew Barrymore, and his siblings Ethel and Lionel also had extensive film careers. John made his stage debut in 1900, and quickly became a matinee idol. He entered films in 1913, thanks to the invention of the cinematograph, and although he eventually gave up the stage, it was really his first true love. His Hamlet was widely acclaimed and plans were made to film it, but they came to nothing.

However, it was thanks to these plans that I first met John Barrymore. I had already played Yorick in two films, opposite Johnston Forbes-Robertson in 1913, and then with Asta Nielsen in 1920. A number of reviewers generously called me the definitive Yorick. Teaming the definitive Yorick with the definitive Hamlet was an obviously good idea but alas, it wasn’t to be. I never actually worked with John, but that may have been for the best, as he was notoriously difficult to work with. At the end of filming Bill Of Divorcement (1940), Katie Hepburn said “Thank goodness I don’t have to act with him anymore!” to which he replied “I didn’t know you ever had!”

However, it was thanks to these plans that I first met John Barrymore. I had already played Yorick in two films, opposite Johnston Forbes-Robertson in 1913, and then with Asta Nielsen in 1920. A number of reviewers generously called me the definitive Yorick. Teaming the definitive Yorick with the definitive Hamlet was an obviously good idea but alas, it wasn’t to be. I never actually worked with John, but that may have been for the best, as he was notoriously difficult to work with. At the end of filming Bill Of Divorcement (1940), Katie Hepburn said “Thank goodness I don’t have to act with him anymore!” to which he replied “I didn’t know you ever had!”

He appeared in so many memorable films – I’ve already discussed Doctor Jekyll And Mister Hyde (1920), and during that very same decade he made several entertaining swashbucklers, but after the early thirties John frequently parodied himself in his own films. It probably comes as no surprise that the more he overacted, the further his career declined. Fortunately, he doesn’t overact in Svengali. John had been a drinker from his teenage years onward and, sadly, alcoholism dominated the last years of his life, but I can personally report that amongst his many talents was his ability to remain devastatingly witty while plastered.

He appeared in so many memorable films – I’ve already discussed Doctor Jekyll And Mister Hyde (1920), and during that very same decade he made several entertaining swashbucklers, but after the early thirties John frequently parodied himself in his own films. It probably comes as no surprise that the more he overacted, the further his career declined. Fortunately, he doesn’t overact in Svengali. John had been a drinker from his teenage years onward and, sadly, alcoholism dominated the last years of his life, but I can personally report that amongst his many talents was his ability to remain devastatingly witty while plastered.

For example, John Barrymore personally chose Marian Marsh to play the role of Trilby, a risky decision that paid off, as this is her career high-point. Prior to this she was an extra and had only a few interesting roles afterwards. Later the same year she was in The Mad Genius (1931), a variation on Svengali, also with Barrymore; and Five Star Final (1931) with Edward G. Robinson and Boris Karloff is also well worth a look. If Marian Marsh had made no other films, Svengali alone would secure her a place in film history. She’s not the best actress to step before the cameras, but she definitely has something, a certain je ne sais quois, and that helmet of blonde hair is very striking indeed.

For example, John Barrymore personally chose Marian Marsh to play the role of Trilby, a risky decision that paid off, as this is her career high-point. Prior to this she was an extra and had only a few interesting roles afterwards. Later the same year she was in The Mad Genius (1931), a variation on Svengali, also with Barrymore; and Five Star Final (1931) with Edward G. Robinson and Boris Karloff is also well worth a look. If Marian Marsh had made no other films, Svengali alone would secure her a place in film history. She’s not the best actress to step before the cameras, but she definitely has something, a certain je ne sais quois, and that helmet of blonde hair is very striking indeed.

Other names of interest include Donald Crisp as the Laird. His film career lasted from 1911 to 1963, including a small part in the infamous and influential Birth Of A Nation (1915), and he directed a few films in the twenties. After the coming of sound he stuck to acting, often playing stern but fair patriarchs, and won the Academy Award for best supporting stern-but-fair patriarch in How Green Was My Valley (1941). I like his performance in Svengali, but the name Donald Crisp wouldn’t have been first in my mind when casting a bohemian artist.

Other names of interest include Donald Crisp as the Laird. His film career lasted from 1911 to 1963, including a small part in the infamous and influential Birth Of A Nation (1915), and he directed a few films in the twenties. After the coming of sound he stuck to acting, often playing stern but fair patriarchs, and won the Academy Award for best supporting stern-but-fair patriarch in How Green Was My Valley (1941). I like his performance in Svengali, but the name Donald Crisp wouldn’t have been first in my mind when casting a bohemian artist.

Playing the small part of Svengali’s first victim is Carmel Myers, a Rabbi’s daughter, who played leads or second leads from 1916 to the late twenties. She didn’t fare so well in Talkies, and her career was in decline by the time she was in Svengali. Then television came to the rescue, just like it has for me, and she continued performing until her death in 1980. Back in 1924, Carmel and I were two of the fifty or so people who attended the only screening of the original nine-hour version of Eric Von Stroheim’s greatest masterpiece Greed (1924). The studio saw no value in a film with two inbuilt sequels, this being some seventy years before The Matrix (1999), so Greed was reduced to just two hours and the cut footage destroyed – and yet the Wachowski Brothers films remain intact. There is no God!

Playing the small part of Svengali’s first victim is Carmel Myers, a Rabbi’s daughter, who played leads or second leads from 1916 to the late twenties. She didn’t fare so well in Talkies, and her career was in decline by the time she was in Svengali. Then television came to the rescue, just like it has for me, and she continued performing until her death in 1980. Back in 1924, Carmel and I were two of the fifty or so people who attended the only screening of the original nine-hour version of Eric Von Stroheim’s greatest masterpiece Greed (1924). The studio saw no value in a film with two inbuilt sequels, this being some seventy years before The Matrix (1999), so Greed was reduced to just two hours and the cut footage destroyed – and yet the Wachowski Brothers films remain intact. There is no God!

Oh dear, I seem to have waffled again, haven’t I? Maybe I should return to John Barrymore and the 1931 masterpiece Svengali quickly before I get sidetracked again. It’s a rather downbeat ending for poor Trilby – did God grant Svengali his dying wish? If so, it’s a highly dubious act of generosity to one who definitely doesn’t deserve it, from a God who still hasn’t spared the rest of us from the dreaded Wachowski Brothers. I’m sure that ending wouldn’t have got past the censors if the film had been made just three years later, when the ridiculously strict Hays Code became compulsory.

Oh dear, I seem to have waffled again, haven’t I? Maybe I should return to John Barrymore and the 1931 masterpiece Svengali quickly before I get sidetracked again. It’s a rather downbeat ending for poor Trilby – did God grant Svengali his dying wish? If so, it’s a highly dubious act of generosity to one who definitely doesn’t deserve it, from a God who still hasn’t spared the rest of us from the dreaded Wachowski Brothers. I’m sure that ending wouldn’t have got past the censors if the film had been made just three years later, when the ridiculously strict Hays Code became compulsory.

I’m well-pleased to have been able to discuss this piece of high quality cinematic art for you. I feel it has restored my artistic credibility. Stop that giggling! Ahem – so watch out for Mad Artists and tread carefully the cobbled streets of not-so-gay Paris, until next week when I return with another daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensation found in that steaming cesspit known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

I’m well-pleased to have been able to discuss this piece of high quality cinematic art for you. I feel it has restored my artistic credibility. Stop that giggling! Ahem – so watch out for Mad Artists and tread carefully the cobbled streets of not-so-gay Paris, until next week when I return with another daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensation found in that steaming cesspit known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Svengali (1931)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews