SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“John and Laura Baxter are living in Venice when they meet a pair of elderly sisters, one of whom claims to be psychic. She insists that she sees the spirit of the Baxters’ daughter, who recently drowned. Laura is intrigued, but John resists the idea. He, however, seems to have his own psychic flashes, seeing their daughter walk the streets in her red cloak, as well as Laura and the sisters on a funeral gondola.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Many film directors make little of much. Nicolas Roeg‘s peculiar talent is to make a great deal out of very little. Typically, Roeg’s films are based on the slightest of source material, and Don’t Look Now (1973) is based on a short story by Daphne Du Maurier. The comparatively simple incidents of the story are transmitted by Roeg into a hauntingly complex work, a web of uncanny displacements in time and space that suggest a geometry of meaningful connections hidden behind the mundane geography of our lives.

Supreme character actor Donald Sutherland plays an art historian and restorer of churches who, at the film’s opening, is studying colour slides of a church interior in Venice. As a strange red blot oozes across the slide, he unexpectedly rises to his feet with a howl of anguish, and rushes outside to where his young daughter, dressed in red, lies drowned in a small lake. He and his wife (beautiful Julie Christie in her prime) go to Venice in the hope that he might lose himself in his work. They meet two rather eccentric old sisters who claim psychic powers and are told that their dead daughter is sending them a message, which the wife half-believes. Everywhere the husband travels in Venice he sees flashes of red in the corner of his eye, the identical red of his daughter’s raincoat. Within the same church which we saw on the slide, the husband nearly falls to his death.

Supreme character actor Donald Sutherland plays an art historian and restorer of churches who, at the film’s opening, is studying colour slides of a church interior in Venice. As a strange red blot oozes across the slide, he unexpectedly rises to his feet with a howl of anguish, and rushes outside to where his young daughter, dressed in red, lies drowned in a small lake. He and his wife (beautiful Julie Christie in her prime) go to Venice in the hope that he might lose himself in his work. They meet two rather eccentric old sisters who claim psychic powers and are told that their dead daughter is sending them a message, which the wife half-believes. Everywhere the husband travels in Venice he sees flashes of red in the corner of his eye, the identical red of his daughter’s raincoat. Within the same church which we saw on the slide, the husband nearly falls to his death.

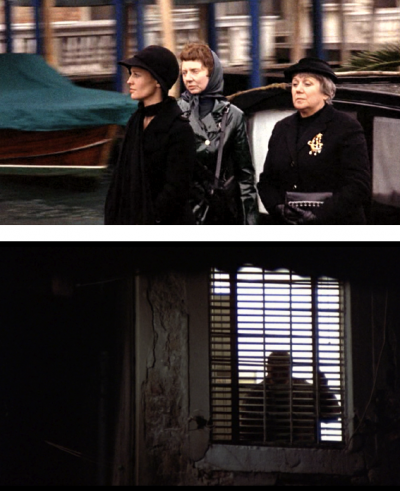

When the young girl was drowning, her brother rode over a pane of glass on his bicycle, and it shattered. In Venice, too, glass shatters more than once. The couple go to bed to make love, but inter-cut with this they are getting dressed to go out – time is telescoped. The husband sees his wife standing on the prow of a funeral barge on a Venetian canal when she is supposed to be in England, he does not know that with his own intermittent second-sight he is witnessing his own subsequent funeral. The two seemingly kind old sisters laugh inexplicably when they are alone, after telling the wife they have seen their daughter in a red raincoat. Are they frauds?

When the young girl was drowning, her brother rode over a pane of glass on his bicycle, and it shattered. In Venice, too, glass shatters more than once. The couple go to bed to make love, but inter-cut with this they are getting dressed to go out – time is telescoped. The husband sees his wife standing on the prow of a funeral barge on a Venetian canal when she is supposed to be in England, he does not know that with his own intermittent second-sight he is witnessing his own subsequent funeral. The two seemingly kind old sisters laugh inexplicably when they are alone, after telling the wife they have seen their daughter in a red raincoat. Are they frauds?

Venice is a gloomy labyrinth, out-of-season, shrouded. Bodies are pulled out of the canals, and someone is committing Jack-The-Ripper-style murders. In a church the wife lights a candle, at the same time the husband tries to switch on a light. In Venice the streets go in wrong directions and he ends up where he began, and the death which has been insistently hinted at since the opening is his own, for the red raincoat turns around and it is a mad old female dwarf with a meat cleaver. A spreading stain of blood engulfs the screen which is, in a way, a colour transparency in itself.

Venice is a gloomy labyrinth, out-of-season, shrouded. Bodies are pulled out of the canals, and someone is committing Jack-The-Ripper-style murders. In a church the wife lights a candle, at the same time the husband tries to switch on a light. In Venice the streets go in wrong directions and he ends up where he began, and the death which has been insistently hinted at since the opening is his own, for the red raincoat turns around and it is a mad old female dwarf with a meat cleaver. A spreading stain of blood engulfs the screen which is, in a way, a colour transparency in itself.

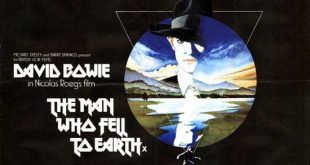

Contributing to the visual look of David Lean’s Lawrence Of Arabia (1962), Roger Corman’s The Masque Of The Red Death (1964), Charles Feldman’s Casino Royale (1967), and co-directing Performance (1970), Nicolas Roeg would later become the guiding force behind such landmark films as Walkabout (1971), The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976), Eureka (1983), and Insignificance (1985). Goodness knows what his version of Flash Gordon (1980) would have looked like if he wasn’t replaced at the last minute by mediocre director Mike Hodges. Roeg has few peers in the art of dazzling editing, so that juxtapositions flare out with meaning. He made motion pictures as if he was the first director in the world to discover colour film, with a joyful freshness in the exultant way he exploits this private discovery.

Contributing to the visual look of David Lean’s Lawrence Of Arabia (1962), Roger Corman’s The Masque Of The Red Death (1964), Charles Feldman’s Casino Royale (1967), and co-directing Performance (1970), Nicolas Roeg would later become the guiding force behind such landmark films as Walkabout (1971), The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976), Eureka (1983), and Insignificance (1985). Goodness knows what his version of Flash Gordon (1980) would have looked like if he wasn’t replaced at the last minute by mediocre director Mike Hodges. Roeg has few peers in the art of dazzling editing, so that juxtapositions flare out with meaning. He made motion pictures as if he was the first director in the world to discover colour film, with a joyful freshness in the exultant way he exploits this private discovery.

Don’t Look Now is quite a titillating title. Because ‘now’ maybe ‘then’? Because ‘looking’ is paradoxically what the film is about? Why shouldn’t we look now? The theme of the film is not so much about telepathy or precognition, as it is about predestination. Personally, I don’t believe in predestination, but I must confess that never before in the cinema has it been so convincingly portrayed, from the very opening scene which has the seeds of every other scene within it. It’s not a film about ghosts as such, it’s a film that evokes an invisible world where our fate is already known, intimations from which occasionally enter our world. By creating a network of meanings and associations, the film convinces us that in some alternate fantastic reality, pieces of a predestined jigsaw puzzle are being put together. These may be pulp metaphysics, but they are brought to life with the most amazing flair.

Don’t Look Now is quite a titillating title. Because ‘now’ maybe ‘then’? Because ‘looking’ is paradoxically what the film is about? Why shouldn’t we look now? The theme of the film is not so much about telepathy or precognition, as it is about predestination. Personally, I don’t believe in predestination, but I must confess that never before in the cinema has it been so convincingly portrayed, from the very opening scene which has the seeds of every other scene within it. It’s not a film about ghosts as such, it’s a film that evokes an invisible world where our fate is already known, intimations from which occasionally enter our world. By creating a network of meanings and associations, the film convinces us that in some alternate fantastic reality, pieces of a predestined jigsaw puzzle are being put together. These may be pulp metaphysics, but they are brought to life with the most amazing flair.

It’s vitally important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because an old blind woman told me that if you don’t read all my reviews from now on, the entire world would be devoured by an enormous Star-Goat. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but she was just so certain, I feel we’d best not take the risk. So enjoy your week, and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

It’s vitally important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because an old blind woman told me that if you don’t read all my reviews from now on, the entire world would be devoured by an enormous Star-Goat. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but she was just so certain, I feel we’d best not take the risk. So enjoy your week, and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews