SYNOPSIS:

“Baron Victor Von Frankenstein has fallen on hard times; he was tortured at the hands of the Nazis for not cooperating with them during World War Two and he is now badly disfigured. As his family’s wealth begins to run out, the Baron is forced to allow a television crew shooting a documentary on his monster-making ancestors to film at his castle in Germany. However, the Baron has some ideas of his own: using the money from the crew’s rent he buys an atomic reactor and uses it to create a hulking monster, transplanting his butler’s brain into the thing and using it to kill off the crew for more spare parts.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

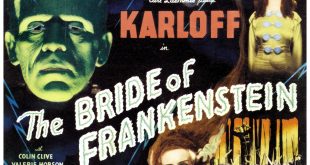

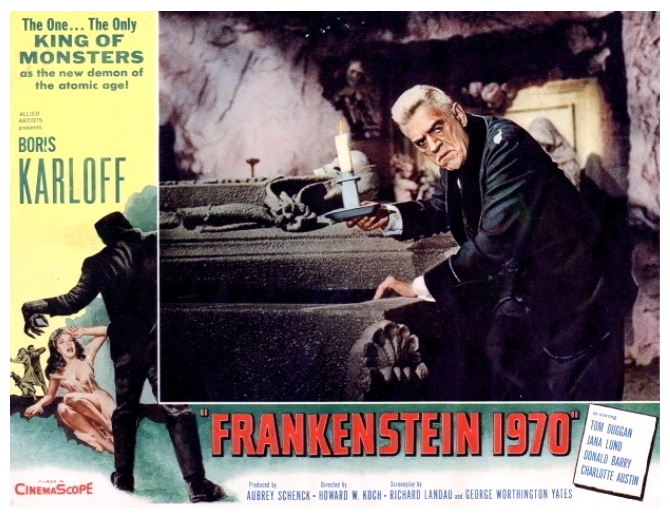

Throughout most of the fifties Frankenstein became conspicuous solely by his absence. After Universal’s comedic send-off Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), the monster hibernated for nearly a decade until a small British film studio decided to branch out from their black-and-white adaptations of radio dramas into the realm of colourful Gothic horror. When Hammer’s The Curse Of Frankenstein (1957) hit American shores, its huge financial success produced a tidal wave of excitement among smaller independent producers. Though the major Hollywood studios held their collective noses and stayed away from such a gruesome and offensive topic, several more adventurous filmmakers decided to temporarily drop the giant insects and invading aliens that flooded the drive-in screens to see if they could jump on this new Frankenstein bandwagon. Updating the Frankenstein legend with atomic reactors and the original monster himself, Boris Karloff, as the good doctor, may have sounded like a good idea at the time, but Frankenstein 1970 (1958) falls flat.

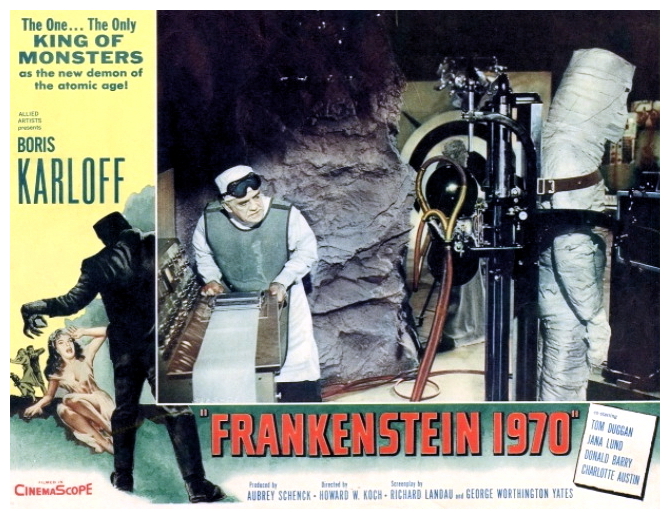

The film was made because producer Aubrey Schenk had signed Karloff up to a three-movie deal: “We had to pay him US$30,000 whether we used him in a picture or not, so we went to the guys at Allied Artists – they wanted pictures – and we made it quickly for them. It was like a pick-up deal. I think we made it for US$110,000 and they paid us US$250,000 for it, an outright buy.” In the film, Karloff plays a contemporary Baron Frankenstein, a victim of torture at the hands of an unspecified (ie Nazi) regime. The original script was titled Frankenstein 1960, just two years in advance of its release but, since nothing is ever made of its futuristic setting, it’s anyone’s guess why the filmmakers ultimately added another decade to the title (one theory states the filmmakers assumed mail-order nuclear devices would not be available until 1970). As the last of the Frankenstein line, Karloff still inhabits the old family castle where he has built an ultra-modern laboratory in a secret room underneath the crypt, with plans to make a new improved version of his infamous ancestral monster. For this he needs an atomic reactor.

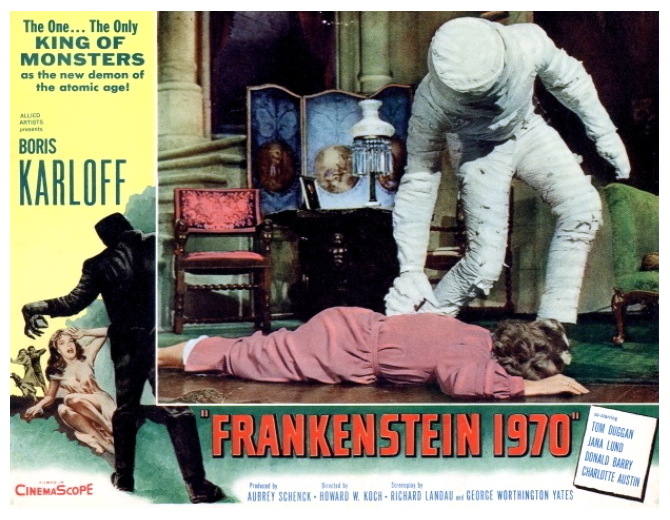

For financial reasons, he allows a pesky television crew to use his castle as the background for their show in exchange for the equipment he needs. When the atomic equipment finally arrives, the Baron revives his monster which proves to be a great disappointment because, instead of a terrifying patchwork ghoul, the monster is simply a large man (Mike Lane) wrapped from head to toe in white bandages – which would later inspire The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) – and on his head is a ridiculous-looking bucket with holes cut out for eyes. Given his appearance and the fact that the monster is blind, he is hardly menacing, and much of the story focuses on the Baron sending the groping creature out to find a suitable pair of eyes. The script gives Karloff little to work with and burdens the veteran horror actor with some real clunkers: “I am now starting up the atomic steam generator,” and “All radiation off, zero on geiger modem dial.”

Frankenstein 1970 was not a stellar moment in Karloff’s career. It’s downright embarrassing, even for such a consummate professional, to wear silly goggles and apron to comment, “Ah, Shuter, yours is not the brain I would have chosen, but at least you are obedient.” In another scene Karloff becomes the butt of an unintentional joke when he clumsily drops the jar containing the monster’s intended eyeballs and comically slaps his thigh in a lame ‘oh bugger’ sort of gesture. Occasionally some of his old menace shines through, however, such as when Karloff tells the story of the inquisitive camp commandant who was found with his tongue cut out but, on the whole, Karloff gives a horribly over-ripe performance, arguably the worst of his entire career. Director Howard Koch realised that Karloff was overdoing it but was unwilling to reel the star in. With only one exception, the supporting cast of characters (and actors) prove completely uninteresting.

The only intriguing personality is Judy (Charlotte Austin), the television director’s feisty secretary and ex-wife. She’s still in love with the abrasive director but spends most of her time fending off an amorous whiny publicity guy. Unfortunately she’s the monster’s first victim and makes her tragic exit halfway through the film. This, by the way, is the source of another unintentionally humorous moment – when the Baron places her body in his oversized customised disposal unit and starts the machine, it sounds like a flushing toilet (the original gruesome crunching sound effects were removed at the request of the censors). Director Howard Koch is both heavy-handed and self-conscious – his idea of clever innovation is to use the sledgehammer approach to pound his ideas into the viewer’s psyche. In one scene the blind monster (still missing a pair of eyes) approaches his victim, Koch first shows the monster’s empty eye-holes, then a shot of the victim’s eyes, and finally a superimposition of the victim’s eyes over the monster’s eye-holes.

The impact of the ironic (if not wholly expected) twist of revealing that the Baron had created his monster in his own image, is nullified by the off-handed shot used to present it. Even producer Schenk admitted the director did a less-than-terrific job but, to be fair, he was given only eight days to shoot it. The film’s predictable ending also proves disappointing. The monster, whose skull houses the brain of a murdered servant, refuses to harm the heroine as ordered (since she had previously been kind to the servant) and consequently turns on his master. As a result, the Baron kills both the monster and himself by releasing lethal radiation in the form of an unconvincing steam cloud. Quite the anti-climax, with the Frankenstein monster killed by radiation poisoning. In Frankenstein 1970, the atomic hysteria of the fifties reached back to claim even Mary Shelley‘s timeless creation. Reviewers were surprisingly mild in their criticism, perhaps out of some sort of respect for Karloff.

“This horror meller (melodrama) should do okay as part of the program. Its suspense is uneven with some of the horror situations pretty strong and others mild. The story by Aubrey Schenk and Charles Moses is confusing at times. The Karloff name, however, should prove an attraction at the box-office. The black-and-white CinemaScope photography is good.” (Motion Picture Exhibitor)

“A competently made production that will do well in its class. Karloff does a careful, convincing job with his role, which is competently written.” (Variety)

“The whole inept effort is a slight on the horrific name of Frankenstein.” (Monthly Film Bulletin)

Enough crying over spilt blood, please join me next week when I have another opportunity to give your cinematic sensibilities a damn good thrashing with the ugly stick for…Horror News! Toodles!

Frankenstein 1970 (1958)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews