SYNOPSIS:

“As a feudal war rages in 14th-century Japan, those left behind are struggling to survive. The wife and the mother of a soldier make their meagre living by preying upon hapless samurai who come their way, killing them and selling their armour for food. When a friend of the soldier returns to the women’s hut, they learn the fate of their soldier, and are forced to deal with this survivor. Tensions build as the young widow gives in to her loneliness, and the older woman fears abandonment, feels jealousy, and plots revenge.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

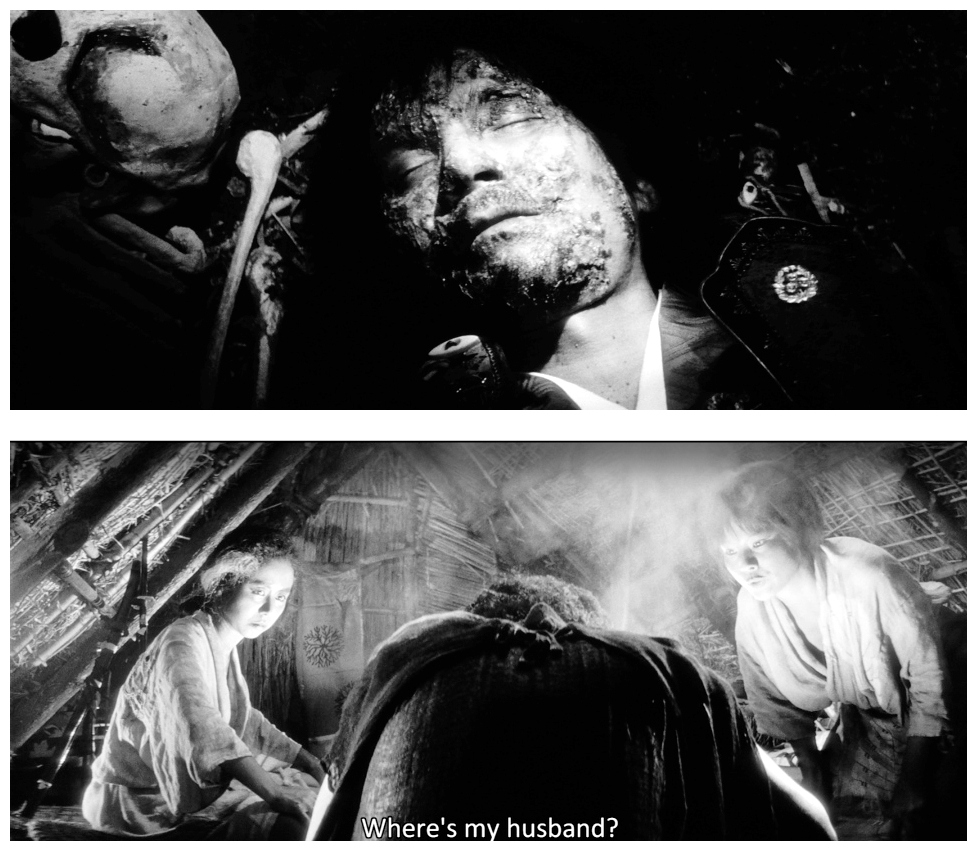

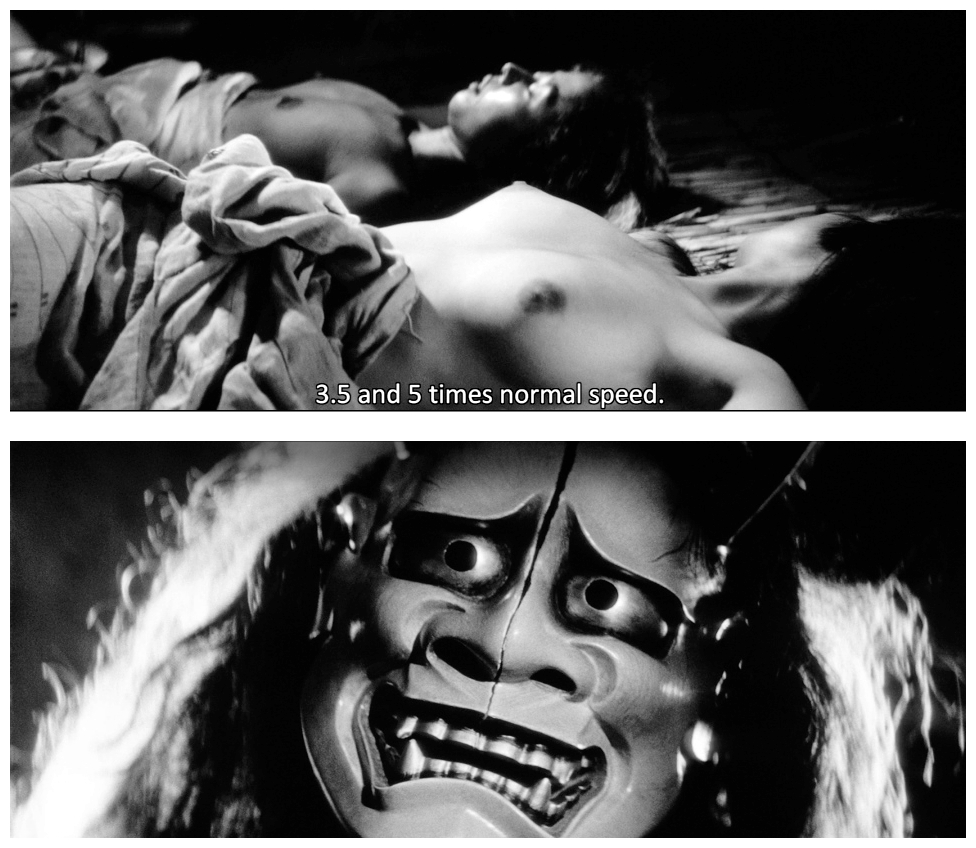

There is a strong tradition of the supernatural in Japan, which often appears in its films. The greatest of these was made in the early fifties – Ugetsu Monogatari (1953) – but two more excellent Japanese fantasies were released a decade later: Kwaidan (1964) and Onibaba (1964) which translates literally as Demon Hag. Written and directed by Kaneto Shindo, Onibaba is set in a sixteenth century Japan reeling from monstrous civil wars. At the heart of a wide sea of placidly waving tall susuki grass reeds, a mother (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law (Jitsuko Yoshimura) scratch a living by robbing the bodies of dead soldiers, which are then dumped into a mysterious hole. The mother steals a demon mask from a disfigured samurai (whom she lures into falling to his death in the hole) and wears it to frighten her daughter away from her sexual liaisons with a lazy layabout neighbour Hachi (Kei Sato).

During a storm, the mother terrifies the daughter with the mask, but Hachi finds the daughter and again has sex with her in the grasses as the mother watches from a distance. Hachi then returns to his hut only to be killed by a man waiting there. The mother discovers that, after getting wet in the rain, the mask is impossible to remove. She reveals her scheming to the daughter and pleads with her to help take off the mask. The daughter agrees to remove the mask after the mother promises not to interfere with her relationship with Hachi. The daughter breaks off the mask with a hammer and, when it is finally ripped from her, the face beneath is horribly disfigured, apparently from smallpox, but we know it is the curse of the demon. Frightened, the daughter runs away with mother in hot pursuit crying, “I am not a demon, I am a human being!” The daughter leaps into the mysterious hole and, as the mother leaps after her, the film concludes.

The story of Onibaba was inspired by a Shin Buddhist parable known as ‘The Bride-Scaring Mask’ or ‘Mask With Flesh Attached’. A mother uses a mask to scare her daughter from going to the temple. She is punished by the mask sticking to her face and, when she begged to be allowed to remove it, she was able to take it off, but it took the flesh of her face with it. Onibaba portrays the outcome of war as a tale of unmitigated horror from the perspective of the losers. In doing so, writer-director Kaneto Shindo makes an allegorical statement about life amid both scarcity and class and gender antagonism, and also reveals the ideological impulses behind the horror genre itself. This is a strong uncanny film which displays a quiet pity towards its protagonists, who are victims as much as monsters, yet the constantly moving, rustling reeds seem to reflect the insubstantiality of their way of life, and its inevitable collapse.

The demon mask is a grotesquely effective symbol of the vengeful spirit of the harridan mother, and also of the cruel wars that were depopulating Japan. By transforming the demon mask into a representation for the disfigured face of the ‘Hibakusha’ (a group of people who were stigmatised after the second world war) it connects generic convention with the all-too-real horrors of post-war Japan. Shindo himself said that the effects of the mask on those who wear it are symbolic of the disfigurement of the victims of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, reflecting the traumatic effect of this visitation on post-war Japanese society. Now it’s time for me to politely invite you to join me again next week when I have another opportunity to scoop out your brain and drop it in a bucket with another spine-tingling journey to the dark side of…Horror News! Toodles!

Onibaba (1964)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews